Sexual health education among undergraduate students of medicine

Introduction

Sexuality occupies a fundamental position in the lives of individuals and is directly related to general health and wellbeing (1). Sexual disorders can be related to multiple pathologies and compromise the quality of life of individuals (2). Thus, the study of sexual health, which is understood as physical, emotional, mental and social wellbeing related to sexuality, should be of interest to health professionals and should be used in the practice of medicine to understand and treat patients in a holistic manner (3).

Besides the impact on quality of life and health, sexual medicine is important due to the considerable interest on the part of patients for information as well as their complaints related to sexual health (4). Studies have shown that most patients would like their physician to ask them questions regarding their sexual history and 20% to 30% of men and 40% of women have complaints of sexual dysfunction (4-6).

However, the sexual health of patients is not regularly addressed during the clinical investigation. In a study analyzing the search for care with regards to specific sexual problems conducted in 29 countries, only 9% of interviewees reported that a physician had inquired about their sexual health in the previous three years, although many patients believe that it is the physician’s role to bring up the topic and feel grateful for having such a dialog (7). These data justify the apprehension and difficulty physicians have in addressing these complaints, despite recognizing the clinical importance of the sexual history. Time constraints during appointments, insufficient knowledge on sexual function and dysfunction, fear of offending the patient and inadequate training in communication skills are frequent barriers physicians encounter when addressing sexual health (8).

The difficulty in discussing the sexual health of patients emerges prior to graduation. Studies have shown that 68.8% of medical students believe that it is important to address and treat sexual concerns, but only 37.6% feel adequately trained for such (9). Dealing with these complaints distresses medical students, especially during internship, when they begin to see patients. This insecurity is likely due to a lack of preparation during the undergraduate course. Indeed, deficiencies are found with regards to the subject of sexual health in the curricula of medical schools. There is a scarcity of programs that go beyond theoretical classes and seminars and focus on the learning and autonomy of the students. There is a lack of training in clinical skills (taking a sexual history, the physical examination, counselling and medical recommendations) as well as a lack of evaluation on the acquisition of skills by students and the impact on patient satisfaction (8). In a study involving 101 medical schools in the United States and Canada, only 31 reported having a specific course for teaching human sexuality and five schools did not indicate a specific teaching format for the subject (10).

This study is justified by the importance of teaching sexual health in undergraduate medical courses as well as the possibility of improving curricular structure, training during a medical education and integral patient care (11). Moreover, there are few studies about sexual health education at Brazilian medical schools (11). Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate sexual health education among undergraduate medical students.

Methods

A descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted with students 18 years of age and older in the fifth and sixth years of the undergraduate course in medicine in 2018. This study received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the São José Rio Preto School of Medicine in the State of São Paulo, Brazil (CAAE 86726418.8.0000.5415) and all participants signed a statement of informed consent.

Data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire addressing the teaching of sexual health in the first four years of the course and how this knowledge affected relationships with patients. The questionnaire specifically addressed the way sexual health was taught, how the students addressed the sexual history of their patients and the difficulties encountered. The questionnaire included biological, social and cultural aspects of sexuality based on studies conducted with physicians and medical students regarding their educational background in sexual health (8,12).

The first part of the questionnaire addressed the teaching of sexual health during the undergraduate course, such as classes on the topic, teaching activities and aspects of sexuality, how the students evaluated the content of the classes and the impact on their education. The scores of class evaluation were categorized in insufficient (of 1 to 5) and sufficient (of 6 to 10).

The second part addressed the practice of sexual medicine in the relationship between the students and patients, the best way to initiate a dialog on sexual health, the frequency with which patients asked about sexuality, the medical specialties in which they addressed the subject and the difficulties they encountered.

Data analysis involved the calculation of descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum). Content analysis was used for the discursive answers. A databank was created with all completed questionnaires. The frequency distribution was calculated based on the number of students who answered each question. The database was organized in Microsoft Excel® 2007 (Microsoft Corp., USA).

Results

One hundred twenty-five students participated in the present study (response rate: 85%). Sixty-nine (85.2%) students in the fifth year and 56 (84.8%) students in the sixth year answered the questionnaire.

Classes and teaching activities

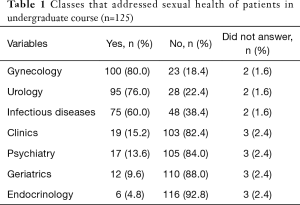

According to 56 (44.8%) students, sexual medicine was taught during the undergraduate course. Of these total, most students (n=30; 53.7%) reported that it was addressed in one to three classes, the most cited of which was gynecology (81.2%), followed by urology (66.7%) and infectious diseases (25%).

Regarding teaching activities, 64 students (54.7%) mentioned theoretical classes, whereas 99 (86.1%) and 77 (66.7%) student reported no practical classes in the infirmary and clinic, respectively. In terms of the aspects of sexuality addressed during the undergraduate course, the predominant focus was on reproduction (70%) and organic diseases (70%). Only 15 students (13%) mentioned classes addressing the sexual health of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) population and only nine students (7.8%) mentioned classes addressing gender identity and gender roles.

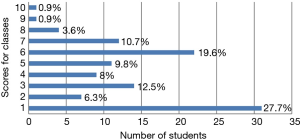

Students’ evaluation of classes

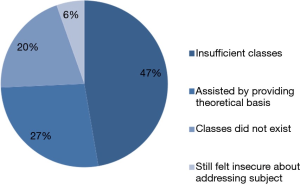

Among the 125 students who answered the questionnaire, 112 (89.6%) attributed a score of 1 to 10 to the classes they took on sexual health during the undergraduate course (Figure 1). The mean score was 4 and the mode was 1.

Among the 74 students who answered the question on the reasons for the scores attributed to the classes, 35 (47.3%) stated that the classes were insufficient and 15 (20.3%) stated that the classes did not exist (Figure 2). According to 20 students, the classes contributed to their education by providing a theoretical basis.

Regarding the use in clinical practice of the knowledge acquired in the classes, 114 students (91.2%) stated whether or not there were improvements in their knowledge and self-confidence in addressing sexual health with patients. The majority (52%) reported that there was no improvement.

Addressing sexual health with patients

The predominant fields in which the sexual health of patients was addressed during supervised patient care were gynecology (81.3%), urology (77.2%) and infectious diseases (61%) (Table 1).

Full table

Among the 102 students who answered the question on the best way to bring up the topic of sexual health with patients, 52 (51%) stated that patients should be asked about their sexual life directly. Only 19 (18.6%) emphasized the need to establish the physician-patient bond before asking about the subject.

One hundred twenty-two students (97.6%) reported the frequency with which they used the skills learned for addressing the sexual history of their patients. A large portion (46.7%) reporting using such skills less than once a month, 12.3% reported using such skills once a week and only 7.4% reported using such skills on a daily basis.

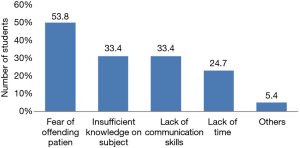

Among the 123 students (98.4%) who answered the question on the difficulties encountered when addressing the sexual health of patients, 62 (50.4%) reported having difficulties. Among the 93 students who listed difficulties, the most frequent was fear of offending the patient (53.8%) and the least frequent was not having time to address the subject (24.7%) (Figure 3).

One hundred twenty-four students rated their confidence in terms of addressing and understanding female and male sexual dysfunctions on a scale of 1 to 10. The means were similar for addressing both male and female patients (5.71 and 5.75, respectively).

Discussion

For the promotion of health and integral care with quality, the Brazilian National Curriculum Guidelines for undergraduate courses in medicine state that the teaching of medicine should value patients in their biological, subjective, ethnic, gender, sexual orientation, environmental and cultural diversity as well as other aspects (13,14). In this context of integral care, sexuality plays a fundamental role in the general health of individuals and sexual health should be a subject that physicians know how to discuss with their patients.

Chronic degenerative, cardiovascular and genitourinary diseases, psychological and psychiatric disorders and an unfavorable socioeconomic status are associated with sexual dysfunction in both sexes (4). In one study, 48% of men and 41% of women believed that a physician should ask about sexual problems during an appointment (7). Therefore, addressing sexual health should be routine in the professional lives of physicians.

In the present study, the majority of students reported having classes in sexual medicine during the undergraduate course. Although this is satisfactory, the subject was addressed in a very restricted manner and did not receive a positive evaluation from the students. The topics were essentially addressed in theoretical classes and not raised much in medical practice, being restricted to the biological aspects of sexuality. This reductionist view impedes physicians from addressing the complaints of the patients with regards to sexual health in a more effective manner (15). A detailed sexual history is necessary to sexual problem assessment and sexual dysfunction diagnosis (16). This finding is in agreement with data described in the literature, which describes a superficial approach to sexual health in medical schools and the need to address more closely the management of sexual dysfunction, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health care and understanding of non-normative sexual practices (17).

In a Brazilian study evaluating how human sexuality was addressed in the medical curriculum, approximately 90% of the 207 professors interviewed reported that the workload destined to the topic corresponded to 6 hours (18). Moreover, the most discussed subjects were sexually transmitted diseases (62.4%) and the anatomy and physiology of the reproductive system (55.4%) (18). These findings show the need to include sexual medicine in the curriculum and address human sexuality not only in terms of organic and pathological aspects. Only then will it be possible to produce health professionals capable of understanding the sexual dysfunctions of their patients.

The present findings show the little inclusion of sexual health during clinic activities. Approximately half of the students stated that their education on this subject during the undergraduate course did not enhance their knowledge or confidence in bringing up the subject with patients. A previous study involving students in Canada and United States found that over 53% of them felt inadequately trained in medical school to address sexual concerns in the clinical context (19). However, this skill should be trained during the undergraduate course. Otherwise, the students fail to include it in their routine care. With regards to raising issues of sexuality when taking the patient history, it is necessary for students to be able to develop competences during their undergraduate education in order to make them feel secure enough to understand their patients’ complaints and define the best course of action (17).

After reviewing the current state of medical education on human sexuality, a study articulated a set of competences that includes knowledge (reproductive biology, anatomy and physiology of human sexual response, the impact of medical illnesses and their treatment upon sexual function, and sexual abuse and violence), skills (taking a sexual history and integrated diagnosis of sexual dysfunction) and attitudes (reflection on personal beliefs and how they may impact patient care) to improve the curricula of medical schools (20).

About patients’ perspectives, they feel that their physicians are reluctant, disinterested, or unskilled in sexual problem management, because there are still barriers encountered by doctors to address the patient sexuality (21). In the present investigation, it is evident that the students feel unprepared and have difficulties asking about the sexual health of patients. The most cited difficulties were fear of offending the patient, insufficient knowledge on the subject and a lack of communication skills. The results show that 46.7% of the students addressed the sexual health of their patients less than once a month during routine care. Moreover, the present findings demonstrate that the students have little confidence in understanding and addressing sexual dysfunction in both sexes. This may be the consequence of the superficial training in sexual medicine they receive in the undergraduate course, which makes it difficult to introduce the subject with patients. However, patients would like to receive sexual health information from their provider who initiates the conversation and feel more comfortable with providers who are knowledgeable about sexual concerns and seem comfortable addressing them (22).

The present findings could foster the discussion on the importance of taking the sexual history of patients to provide integral care. Theoretical and practical classes in sexual health should be offered in all years of the course to furnish students with a sufficient basis on which to address the sexual dysfunctions of their patients.

Considering the importance of sexual health to overall wellbeing, the multiple aspects of human sexuality and the occurrence of sexual dysfunctions in the population, the teaching of sexual medicine in medical courses is fundamental. The limited discussion of these aspects in routine care is contrary to the guidelines established for a medical education. It is necessary to provide a broad theoretical basis, including the development of skills for clinical practice in order to prepare physicians to address these issues.

Conclusions

The present findings demonstrate that knowledge of students regarding sexual health in undergraduate courses is insufficient, as evidenced by deficiencies in teaching and difficulties in addressing the subject with patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the São José Rio Preto School of Medicine in the State of São Paulo, Brazil (CAAE 86726418.8.0000.5415) and all participants signed a statement of informed consent.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Mulhall J, King R, Glina S, et al. Importance of and satisfaction with sex among men and women worldwide: results of the global better sex survey. J Sex Med 2008;5:788-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan HM, Tong SF, Ho CC. Men's health: sexual dysfunction, physical, and psychological health—is there a link? J Sex Med 2012;9:663-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Developing sexual health programmes: A framework for action (No. WHO/RHR/HRP/10.22). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010.

- Lewis RW, Fugl‐Meyer KS, Corona G, et al. Definitions/epidemiology/risk factors for sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 2010;7:1598-607. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meystre-Agustoni G, Jeannin A, de Heller K, et al. Talking about sexuality with the physician: are patients receiving what they wish? Swiss Med Wkly 2011;141:w13178. [PubMed]

- Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:970-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moreira ED, Brock G, Glasser DB, et al. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract 2005;59:6-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parish SJ, Rubio-Aurioles E. Education in sexual medicine: proceedings from the international consultation in sexual medicine, 2009. J Sex Med 2010;7:3305-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wittenberg A, Gerber J. Recommendations for improving sexual health curricula in medical schools: results from a two-arm study collecting data from patients and medical students. J Sex Med 2009;6:362-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solursh DS, Ernst JL, Lewis RW, et al. The human sexuality education of physicians in North American medical schools. Int J Impot Res 2003;15:S41-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Facio FN Junior, Glina S, Torres LO, et al. Educational program on sexual medicine for medical students: pilot project in Brazil. Transl Androl Urol 2016;5:789-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clegg M, Pye J, Wylie KR. Undergraduate training in human sexuality—evaluation of the impact on medical doctors' practice ten years after graduation. Sex Med 2016;4:e198-208. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Conselho Nacional de Educação (National Council for Education) Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Medicina. Establishes the National Curriculum Guidelines for Undergraduate Medical Programs. Diário Oficial da União 2014;1:8-11. (The Brazilian Official Gazette).

- da Cruz KT. A formação médica no discurso da CINAEM. Dissertação (Mestrado): Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP); 2004.

- World Health Organization. Measuring sexual health: conceptual and practical considerations and related indicators. 2010. Available online: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70434

- Hatzichristou D, Kirana PS, Banner L, et al. Diagnosing sexual dysfunction in men and women: sexual history taking and the role of symptom scales and questionnaires. J Sex Med 2016;13:1166-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shindel AW, Baazeem A, Eardley I, et al. Sexual health in undergraduate medical education: existing and future needs and platforms. J Sex Med 2016;13:1013-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rufino AC, Madeiro A, Girão MJBC. Sexuality education in Brazilian medical schools. J Sex Med 2014;11:1110-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shindel AW, Ando KA, Nelson CJ, et al. Medical student sexuality: how sexual experience and sexuality training impact U.S. and Canadian medical students' comfort in dealing with patients' sexuality in clinical practice. Acad Med 2010;85:1321-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shindel AW, Parish SJ. CME Information: sexuality education in North American medical schools: current status and future directions (CME). J Sex Med 2013;10:3-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parish SJ, Clayton AH. Continuing Medical Education: Sexual Medicine Education: Review and Commentary (CME). J Sex Med 2007;4:259-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wittenberg A, Gerber J. Education: Recommendations for improving sexual health curricula in medical schools: results from a two‐arm study collecting data from patients and medical students. J Sex Med 2009;6:362-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]