Psychosocial impact of penile carcinoma

Introduction

Malignant diseases of the penis are rare in the western world with an incidence of less than 1 in 100,000 men (1). However, these rates are 5 times higher in the developing nations such as Africa and South America, reflecting a higher prevalence of human papilloma virus (HPV) (2). The treatments for early stage disease typically include organ preservations strategies. Conversely, in invasive disease, the gold standard therapy is surgical resection with a partial or radical penectomy (1,3). The diagnosis of carcinoma of the penis along with these more radical disfiguring treatments may have a significant impact on the patient’s sexual function, quality of life, self-image and self-esteem (4). Herein, in this review, we summarized the current literature on the psychological impact of a penile cancer diagnosis and its treatment for patients.

Sexual function and satisfaction after conservative treatment

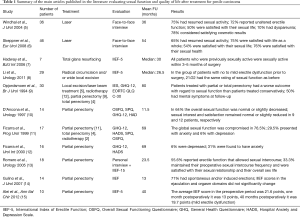

Sexual dysfunction and its effects on the psyche can significantly vary based on the treatment patients received (Table 1). Different surgical organ-preserving treatments are possible for non-invasive disease, including laser therapy, topical therapy, Moh’s micrographic surgery and glans resurfacing.

Full table

In a series of patients who underwent laser treatment for penile carcinoma, 30/40 (75%) patients who were sexually active prior to treatment reported to have resumed activity after treatment (5). Of the entire cohort analyzed, using the Fugl-Meyer Life Satisfaction Check List score (LiSat-11), 23/46 patients (50%) reported satisfaction with their sexual life after laser treatment. Only 3 patients (10%) reported dyspareunia affecting sexual activity.

A retrospective interview-based Swedish study after laser treatment for penile carcinoma in situ (CIS), in 46 out of 67 surviving patients with a mean age of 63 years, reported a marked decrease in some sexual practices, such as manual or oral stimulation, but a general satisfaction rate with life overall, including their sex life, similar to that of the general Swedish population (6).

In a large study on CO2 laser treatment of penile cancer in 224 patients, complaints regarding changes in erection capability or functional impairment in sexual activity were never reported following treatment (16). In another study, no sexual dysfunction occurred in 19 patients who underwent laser treatment (17).

These studies show that sexual function and sexual satisfaction are only marginally reduced after laser treatment of penile carcinoma, and the cosmetic results, judged by the patients themselves, are highly satisfactory. However, there is a risk of clinically manifested dyspareunia and, to some degree, decreased sexual interest.

Glans resurfacing is an alternative to laser treatment for superficial non-invasive disease. In one study with ten patients (7), seven out of ten completed questionnaires [International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5)] and a non-validated 9-item questionnaire at their six-month follow-up visit. There was no erectile dysfunction according to the median IIEF-5 score of 24. All patients who were sexually active before treatment were active again within three to five months. According to the non-validated questionnaire, all patients stated that the sensation at the tip of their penis was either no different or better after surgery and that they had erections within two to three weeks of surgery. Six out of seven patients had sexual intercourse within three months of surgery and five out of seven patients felt that their sex life had improved. Overall patient satisfaction with glans resurfacing was high.

Sexual function and satisfaction after radical treatment

A large portion of patients with carcinoma of the penis will require more aggressive intervention, with two opposite goals: oncological control for the cancer and preservation of sexual function.

Traditional surgical treatment of penile carcinoma was amputation of the glans penis 2 cm proximal to the tumor. Two studies reported sexual function after glansectomy (8,18). In one study (n=68), 79% did not report any decline in spontaneous erection, rigidity and penetrative capacity after surgery, while 75% reported recovery of orgasm (18). In another study (8), all twelve patients had returned to “normal” sexual activity one month after surgery.

Sexual function after partial penectomy was reported in a few small studies. In a series of 18 patients treated with partial penectomy, with a median flaccid penile length of 4 cm post operatively, Romero et al. identified 55.6% of patients having reported erectile function suitable for intercourse post treatment, using the IIEF-15 survey (13). In those patients without sexual activity, 50% reported the main reason was a feeling of shame owing to the small penis size and absence of the glans. Furthermore, while more than half of the patients continued sexual activity, only a third maintained their preoperative frequency of intercourse. This study, while limited by its small number, clearly demonstrated a decrease in sexual function for patients undergoing partial penectomy that led to self-esteem concerns for these patients, with 12/18 (66.6%) patients having reduced overall satisfaction postoperatively.

In a similar study of 14 patients, D’Ancona and colleagues used the Overall Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (OSFQ) and identified 5 patients (36%) having decreased or no sexual function after partial penectomy. In their cohort of patients, no significant levels of anxiety or depression were reported (10).

Ficarra et al. in a series of 17 patients (15 treated with surgical intervention and 2 with radiotherapy) identified compromised sexual function in 76.5% of their patients, also using the OSFQ scale. As would be expected, they identified that patients with more mutilating treatment reported worse function and 35% reporting limitations in their state of health as well as social problems (11). However, Alei et al. showed an improvement in erectile function over time in a series of ten patients (15).

Distal reconstruction of the glans using distal urethra has been reported in a series of 14 patients (14). All patients noticed subjective and objective thermal and tactile epicritic sensibility in the area of the neoglans. Ten of 14 patients (71%) noticed spontaneous and/or induced rigid erections. Interestingly, IIEF scores in the ejaculation and orgasm domains did not significantly change in the period before and after surgery.

There is very limited data about total phallic reconstruction (19-21) following full or near-total penile amputation. It is not possible to restore function, but cosmetically acceptable results are obtainable.

Quality of life

Several qualitative and quantitative instruments were used in the literature to assess “psychological behavior and adjustment” and “social activity” as quality of life indicators.

Opjordsmoen et al. included 30 patients followed up for a median of 80 months after treatment: local excision/laser beam treatment in 5, radiotherapy in 12, partial penectomy in 9, total penectomy in 4 (9). Patients underwent a semi-structured interview and completed the Impact of Events Scale, General Health Questionnaire and the EORTC QLQ C-30 questionnaire. Patients treated with partial or total penectomy had a worse outcome with regard to sexual function than patients treated conservatively, but there was no difference in the other domains of quality of life, indicating that even the more radically treated patients usually adapted adequately. Half of the individuals had mental symptoms at follow-up, and these patients were less satisfied and showed less social activity. Seven men reported that, if asked again, they would choose treatment with lower long-term survival to increase the chance of remaining sexually potent, but the majority gave priority to higher long-term survival.

Ficarra et al. used the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HADS) to analyze the effects of urologic malignancies and their treatments on the patient’s well-being (12). These levels were compared to those of patients undergoing treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia. They did identify significant differences between the malignancy group and the control group in levels of anxiety, but not in levels of depression. Of the patients they studied, 16 had squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. They identified 6% (1/16) of patients to be depressed. They analyzed the anxiety levels after surgical intervention and 31% (5/16) of patients who underwent partial penectomy were found to have anxiety. The depression levels were comparable to the other urologic malignancies, such as renal cell carcinoma, prostate cancer and urothelial carcinoma, but the anxiety levels were more than double compared to patients undergoing other procedures for urologic malignancies, like radical cystectectomy which was associated with 15% of anxiety (8/54). They concluded that patients undergoing partial penectomy for squamous penile carcinoma showed significant impairment in their general state of health, with anxiety being the most significant, compared with controls being treated for benign or other malignant disease.

In a similar study, D’Ancona et al. analyzed 14 patients after partial penectomy with no significant findings of anxiety and depression using the GHQ-12 and HAD questionnaires, respectively (10). “Social activity” remained the same after surgery in terms of living conditions, family life and social interactions. They did identify the greatest difficulty men faced in the first 3 months after surgery to be the difficulties with sexual activity and the discomfort with sitting to urinate. Patients reported fears of mutilation and of loss of sexual pleasure, as well as fear of dying and what this would mean for their families. The most common response in what helped men to overcome their issues was the encouragement of their wives and families.

Interestingly, when looking at the men’s experiences of penile cancer surgery using interviews, Witty et al. identified variable responses, making it difficult for health professionals to judge how surgery will impact on a man presenting to them (22). Those men who were able to return to sexual activity did report a difference in sensation, but still pleasurable. Furthermore, the concern for several patients was the inability to please their partner and this was more bothersome than the inability to please themselves.

It is clear from these studies that treatment of patients with penile cancer affects their sexual function. The effects on sexual function in part can lead to the worsening psychological well-being of these patients.

Conclusions

In patients with long-term survival after penile cancer, sexual dysfunction, voiding problems and cosmetic penile appearance may adversely affect the patient’s quality of life. Although there is little data in the literature about psychosocial impact of penile carcinoma, organ-preserving treatment seems to allow for better quality of life and sexual function and should be offered to all patients whenever feasible.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Hakenberg OW, Compérat EM, Minhas S, et al. EAU guidelines on penile cancer: 2014 update. Eur Urol 2015;67:142-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC. Penile carcinoma: a challenge for the developing world. Lancet Oncol 2004;5:240-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice GUidelines in Oncology - Penile Cancer (Version 2.2017). 2017. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/penile.pdf

- Maddineni SB, Lau MM, Sangar VK. Identifying the needs of penile cancer sufferers: a systematic review of the quality of life, psychosexual and psychosocial literature in penile cancer. BMC Urol 2009;9:8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Windahl T, Skeppner E, Andersson SO, et al. Sexual function and satisfaction in men after laser treatment for penile carcinoma. J Urol 2004;172:648-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skeppner E, Windahl T, Andersson SO, et al. Treatment-seeking, aspects of sexual activity and life satisfaction in men with laser-treated penile carcinoma. Eur Urol 2008;54:631-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hadway P, Corbishley CM, Watkin NA. Total glans resurfacing for premalignant lesions of the penis: initial outcome data. BJU Int 2006;98:532-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li J, Zhu Y, Zhang SL, et al. Organ-sparing Surgery for Penile Cancer: Complications and Outcomes. Urology 2011;78:1121-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Opjordsmoen S, Fosså SD. Quality of life in patients treated for penile cancer. A follow-up study. Br J Urol 1994;74:652-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Ancona CA, Botega NJ, De Moraes C, et al. Quality of life after partial penectomy for penile carcinoma. Urology 1997;50:593-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ficarra V, Mofferdin A, D'Amico A, et al. Comparison of the quality of life of patients treated by surgery or radiotherapy in epidermoid cancer of the penis. Prog Urol 1999;9:715-20. [PubMed]

- Ficarra V, Righetti R, D'Amico A, et al. General state of health and psychological well-being in patients after surgery for urological malignant neoplasms. Urol Int 2000;65:130-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Romero FR, Romero KR, de Mattos MA, et al. Sexual function after partial penectomy for penile cancer. Urology 2005;66:1292-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gulino G, Sasso F, Falabella R, et al. Distal urethral reconstruction of the glans for penile carcinoma: results of a novel technique at 1-year of followup. J Urol 2007;178:941-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alei G, Letizia P, Sorvillo V, et al. Lichen sclerosus in patients with squamous cell carcinoma. Our experience with partial penectomy and reconstruction with ventral fenestrated flap. Ann Ital Chir 2012;83:363-7. [PubMed]

- Bandieramonte G, Colecchia M, Mariani L, et al. Peniscopically controlled CO2 laser excision for conservative treatment of in situ and T1 penile carcinoma: report on 224 patients. Eur Urol 2008;54:875-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Bezooijen BP, Horenblas S, Meinhardt W, et al. Laser therapy for carcinoma in situ of the penis. J Urol 2001;166:1670-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Austoni E, Guarneri A, Colombo F, et al. Reconstructive Surgery for Penile Cancer with Preservation of Sexual Function Eur Urol 2008;7:116. (Abstract 183).

- Garaffa G, Raheem AA, Christopher NA, et al. Total phallic reconstruction after penile amputation for carcinoma. BJU Int 2009;104:852-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gerullis H, Georgas E, Bagner JW, et al. Construction of a penoid after penectomy using a transpositioned testicle. Urol Int 2013;90:240-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hage JJ. Simple, safe, and satisfactory secondary penile enhancement after near-total oncologic amputation. Ann Plast Surg 2009;62:685-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Witty K, Branney P, Evans J, et al. The impact of surgical treatment for penile cancer -- patients' perspectives. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2013;17:661-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]