The impact of insurance status on the survival outcomes of patients with renal cell carcinoma

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common form of kidney cancer among adults. The global incidence and mortality rates of RCC have been increasing by 2–3% every decade (1). The 5-year survival rate in patients with advanced RCC is extremely low, ranging from 5–10%, because of recurrence and distant metastasis (2). Over the past decades, although medical treatment for RCC has great progress which transitioned from a surgical resection approach, to targeted therapy incorporates both surgical and systemic therapies, and now combining novel immunotherapy agents (3). However, despite these recent advances, RCC patients can still expect a dire prognosis

A study reported that nearly 30% of all survivors of cancer reported cancer-related financial problems (4). Recently, a considerable literature has grown up around the health insurance as indicative of the financial capacity which has been shown to be associated with treatment and survival gap in various diseases, including cancer (5). Several studies have demonstrated that uninsured cancer patients present with more advanced disease, thus experiencing worse survival outcomes (6-8). In addition, a study on patients with gallbladder cancer revealed the insurance status of patients as an independent prognostic factor (9). Data from 2004 to 2012 National Health Interview Survey in United States shown that approximately 17% among population under 65 years old live without insurance (10,11). For RCC, treatment patterns with a large shift and associated costs with marked increased in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) patients with private insurance from 2004 to 2011 (12). It has been reported that insurance status may be an important factor for survival outcomes in RCC (13); however, the relationship between insurance status and prognosis in RCC has yet to be fully explored.

Therefore, in this study, we explored the impact of insurance status on the survival outcomes of RCC patients using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer registry database. We hypothesized that insurance status was associated with better CCS compared with those without insurance among the RCC patients. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tau-20-1045).

Methods

Data source

This study retrospectively analyzed the open-access SEER database, run by the US National Cancer Institute, collects and reports patient demographic and cancer incidence and survival data from 18 population-based cancer registries. The dataset analyzed in this study was documentation version April 2017, which collects patients diagnosed 1973–2014 and covers about 30% of the US population. Using the reference number ‘11039-Nov2017’, we obtained and extracted all primary data from the SEER database using SEER*Stat Version 8.3.2. Because the data extracted from this database were anonymized and de-identified before being published, our study did not require informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The details of the study were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of The Fourth Affiliated Hospital (Harbin, China).

Study population

Our study included individuals who had tumors with a primary site of ‘kidney and renal pelvis’ [code C64.9 and C65.9, according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology 3rd Edition (ICD-O-3)]. Patients with common histologic subtypes (clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe renal carcinoma) were included. Histologic confirmation of RCC was determined according to the ICD-O-3, based on the following codes: clear cell (8310, 8320, 8316), papillary (8050, 8260, 8342), and chromophobe (8270, 8290, 8317). Because the database only began to report insurance status in 2007, patients who were diagnosed before 2007 were excluded from the analysis. All of the included patients were diagnosed between 2007 and 2014. Any patients meeting the following criteria were excluded: (I) unknown insurance status; (II) a previous primary tumor; (III) aged <18 or >65 years at diagnosis; or (IV) an autopsy or death certificate was the only reporting source.

A total of 30,951 eligible RCC patients were included. Patient demographic characteristics and clinical variables included: age at diagnosis, gender, race, histotype, grade, tumor size, SEER stage, TNM (tumor, node, and metastasis) stage, and surgical therapy. Race was classified as white, black, or other (American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander). TNM stage was assessed according to the 6th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. Treatment strategies were classified as binary values; namely, surgical therapy (i.e., surgery and/or radiotherapy), or no treatment (due to lack of relevant information on chemotherapy or systemic therapy). We extracted median household income data using the country attributes ACS-2010-2014 datasets. Education level represents the percentage of adult individuals with at least a bachelor’s degree. Marital status was classified into four groups including (married, single, separated/divorced, or widowed). Insurance status was classified as insured, any form of Medicaid, or uninsured.

Statistical analysis

Cancer-specific survival (CSS) was the endpoint of this study. In terms of cause-specific survival, deaths attributed to RCC were considered as events, while deaths from other causes or survival were treated as censored events. To provide descriptive statistics for continuous variables, the patients were divided into categories based on the variable: age was divided into two categories according to the median, median household income and education levels were converted into categorical variables according to the interquartile range (IQR). The baseline characteristics of patients stratified by their insurance status were analyzed with χ2 tests. The Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test were employed to compare each factor of CSS. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using univariate and multivariate Cox regression models. Stratified analysis to examine the impact of insurance status on the outcomes of RCC patients was performed according to SEER stage and racial group. SPSS Version 21.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to carry out all statistical analyses. All tests were two-sided, and the significance level was set at P<0.05.

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

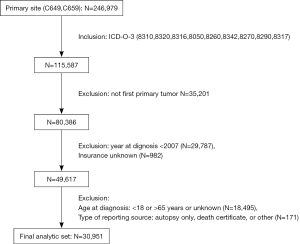

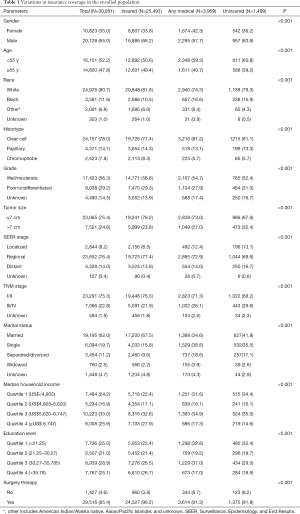

A total of 246,979 individuals with kidney cancer were included in the SEER registries. After the exclusion criteria had been applied, there were 30,951 RCC patients deemed eligible for inclusion. Figure 1 shows the flow chart for patient selection in this study. Of these patients, 25,493 (82.37%) were insured, 3,959 (12.79%) had any form of Medicaid, and 1,499 (4.84%) were uninsured. The clinicopathological characteristics and demographics of patients with different insurance statuses are summarized in Table 1. Among the included RCC patients, 20,128 (65.0%) were male and 24,976 (80.7%) were white, which reflects the higher risk of RCC in white males. The enrolled individuals had a median age of 55 years old. Interestingly, every subgroup was significantly different (all P<0.001). Individuals in the uninsured group were more likely to have poorly-differentiated/undifferentiated tumors as well as larger tumor size (>7 cm) compared to the insured group. The uninsured group also tended to be at a later stage of cancer at the time of diagnosis and were less likely to receive surgical therapy.

Full table

Insurance status and RCC

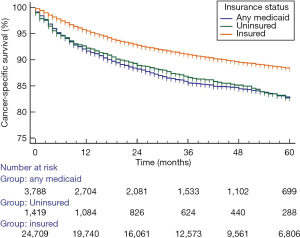

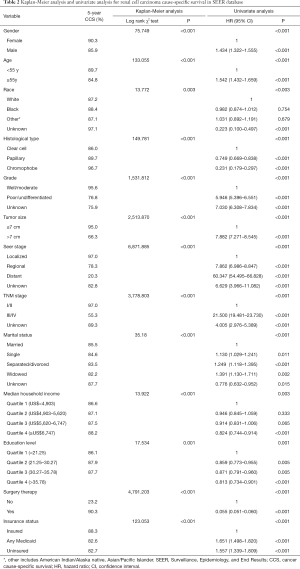

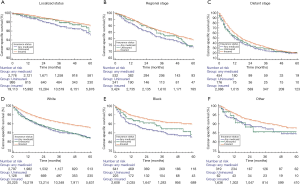

The overall median survival was 34 months, and the 5-year CSS was 87.4%. Moreover, the insured patients (88.3%) had the highest 5-year RCC CSS rate (compared with 82.7% and 82.6% for the uninsured patients and any Medicaid patients, respectively). The CSS curves were analyzed according to insurance status using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test, which showed significant differences (P=0.001) (Figure 2). Univariate analysis revealed that all variables had significant differences between the groups (P<0.05; Table 2). Compared with insured patients, the any Medicaid and uninsured groups had poorer CSS (HR, 1.651; 95% CI, 1.498–1.820) and (HR, 1.557; 95% CI, 1.339–1.809) respectively.

Full table

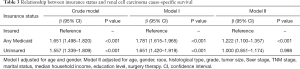

Multivariate analysis was performed to analyze the effect of independent factors on patients’ survival (Table 3). After adjustments for age and gender, the results showed that patients with any Medicaid and uninsured had poorer CSS than insured patients (HR, 1.781; 95% CI, 1.615–1.965 and HR, 1.651; 95% CI, 1.420–1.919, respectively). Adjustments were also made for age, gender, race, histological type, grade, tumor size, Seer stage, TNM, marital status, median household income, education level, and surgical therapy. The results showed that patients with any Medicaid still had poorer CSS than insured patients, (HR, 1.222; 95% CI, 1.100–1.357); however, uninsured patients did not experience worse outcomes (HR, 1.000; 95% CI, 0.851–1.174).

Full table

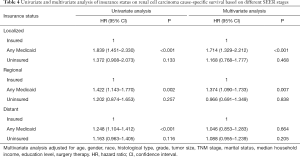

Subgroup analysis of insurance status of RCC patients based on SEER stage

Stratified analysis was performed to explore the impact of insurance status on RCC CSS at each SEER stage (Table 4 and Figure 3A,B,C). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed significant differences (P<0.05) between the three insurance status subgroups at each SEER stage. According to the results of the univariate analysis, patients with any Medicaid had worse survival outcomes than insured patients at each stage (localized stage: HR, 1.839, 95% CI, 1.451–2.330, P<0.001; regional stage: HR, 1.422, 95% CI, 1.143–1.770, P=0.002; distant stage: HR, 1.248, 95% CI, 1.104–1.412, P<0.001). However, univariate analysis did not identify significant differences between insured and uninsured individuals at each SEER stage (localized stage: P=0.133; regional stage: P=0.257; distant stage: P=0.116). Multivariate Cox regression analyses for each SEER stage were then performed to explore the impact of insurance status on RCC CSS. The results confirmed that the Medicaid patients in the localized and regional stage subgroups had the worst survival outcomes (localized stage, HR, 1.714, 95% CI, 1.329–2.212; regional stage, HR, 1.374, 95% CI, 1.090–1.733).

Full table

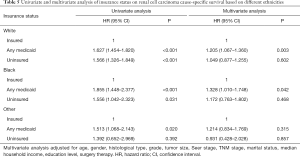

Subgroup analysis of insurance status on RCC according to racial group

The relationship between insurance status and CSS survival was further explored according to patients’ race (see Table 5 and Figure 3D,E,F). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed significant differences (P<0.05) between the three insurance status subgroups in each racial group. As shown in Figure 3, insured individuals in all subgroups had the highest 5-year CSS compared to uninsured individuals and those on any form of Medicaid. Univariate analysis also revealed that insured patients had better outcomes (for white patients, any Medicaid: HR, 1.627, 95% CI, 1.454–1.820; uninsured: HR 1.566, 95% CI, 1.326–1.849; for black patients any Medicaid: HR, 1.855, 95% CI, 1.448–2.377; uninsured, HR 1.556, 95% CI, 1.042–2.323). Multivariate analysis confirmed that patients with Medicaid experienced poorer survival outcomes (for white individuals: HR, 1.205, 95% CI, 1.067–1.360; for black individuals: HR, 1.328, 95% CI, 1.010–1.748).

Full table

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that tumor grade, histology, T stage and N stage are independent predictors of survival in RCC (14,15). Numerous molecular markers such as E-cadherin, C-reactive protein (CRP), PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) (cell cycle), Ki67 (for proliferation), p53, carbonic anhydrase IX (CaIX), hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), and osteopontin (OPN) have also been investigated to determine their impact on the survival outcomes of RCC patients (16). However, none of these markers have improved the predictive accuracy of the current prognostic systems, and they have not been recommended for use in routine clinical practice (17). In recent years, several studies have highlighted the relevance of sociodemographic factors to the survival of patients with various cancers, including genitourinary malignancies (18-20). One previous study revealed marital status to be an important prognostic factor and showed that marriage can improve survival outcomes for patients with RCC (21). In this study, we explored the relationship between the insurance status and survival outcomes of patients with kidney cancer.

Firstly, we result demonstrated sex, age, race, marital status, SEER stage, TNM stage, tumor histology, and income all showed significance differences according to insurance status (P<0.001 for all). In our study, patients with insurance were more likely to have high incomes and education levels. They were also more likely to be male, older, and white. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies based on information from the SEER database (9). Additionally, insured patients experienced better CSS outcomes compared to patients with any form of Medicaid. Even after adjusting for sex, age, race, tumor grade, tumor pathological grade, tumor size, histological type, SEER stage, and surgical therapy, insured patients (88.3%) still had a better 5-year CSS than patients with any form of Medicaid (82.6%). In our stratified analysis of the different SEER stages and racial groups, we found that within the SEER localized stage and the white racial group, having any form of Medicaid insurance was an independent predictor of an unfavorable survival outcome. However, due to insufficient information, we cannot investigate the potential risk factors, such as genetic characteristics, surgical procedures and hospitalizations, and comorbidities, further. Differences in social characteristics, as well as cultural, biological, psychological, and environmental factors, between the individuals included in our study may have resulted in heterogeneity and impacted the results. Further large-scale studies are necessary to explore the mechanisms underlying the relationship between insurance status and survival outcomes.

The survival benefit for insured RCC patients may result from multiple factors. Firstly, insurance status can be considered as an indirect index of the socioeconomic status of the patient, usually indicating that the patient has financial and social support sufficient for acquiring a better level of home and hospital care. Secondly, insured patients have greater access to cancer screening, which can decrease the prevalence and increase the early detection rate in female-specific cancers, such as breast and cervical cancer, which can also prolong the lifetime of the patients (22). Finally, insured patients tend to have a lifestyle that includes fewer cancer risk factors, such as excessive alcohol consumption and smoking (23), which thereby decreases the incidence of cancers of the digestive, respiratory and genitourinary systems. Insurance status has already been proved to be an important factor in obtaining cancer information and screening tests (24). Patients with Medicaid or no insurance have been shown to experience significantly poorer survival outcomes for several malignancies such as melanoma, pancreatic exocrine carcinoma, and certain leukemias (25-27). The explanation offered for this is that uninsured and Medicaid patients are less likely to receive appropriate cancer screening and timely access to medical care (28-31). Moreover, patients without insurance or on Medicaid often have low incomes, and are less likely to be employed or self-employed, less likely to marry or have a stable lifestyle, and more likely to be recent immigrants (32). In our study, patients on any form of Medicaid had poorer survival rates than patients with insurance. However, according to multivariate analysis, there was no significant difference between uninsured and insured patients (P=0.162).

There are several limitations of our study. Firstly, because of the study’s retrospective nature, it was not possible to avoid statistical bias which could potentially impact the accuracy of the results. Secondly, the SEER data does not provide information regarding adjuvant therapy, which may have significantly impacted the survival period of patients with RCC. Thirdly, detailed information on patient insurance, such as the duration of insurance, are not available from the SEER database. Finally, this conclusion should be cautiously extrapolated to Chinese population, due to the two countries exhibit difference the supply of medical services and be in different economic development (33). These limitations may have led to some inaccuracy; however, the large sample size overrides some of these biases to demonstrate the underlying general trend.

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the effects of insurance status on survival outcomes among RCC patients. Compared to uninsured patients and those on any form of Medicaid, insured patients had the highest 5-year RCC CSS. Stratified analysis revealed that for those within the localized tumor stage group or the white racial group, having any form of Medicaid insurance independently predicted an unfavorable survival outcome. Insured RCC patients experienced survival benefits, whilst those on Medicaid suffered poor survival outcomes. Future investigations are needed to validate these findings and explore the underlying mechanisms of poor CSS in Medicaid patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The study supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Provincial Universities (2018-KYYWF-0540).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tau-20-1045

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tau-20-1045). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Because the data extracted from this database were anonymized and de-identified before being published, our study did not require informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The details of the study were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of The Fourth Affiliated Hospital (Harbin, China).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, et al. Epidemiologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a literature review. Cancer Treat Rev 2008;34:193-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhong J, Wah TM. Renal ablation: current management strategies and controversies. Chin Clin Oncol 2019;8:63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lucarelli G, Ferro M, Ditonno P, et al. The urea cycle enzymes act as metabolic suppressors in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Transl Cancer Res 2018;7:S766-9. [Crossref]

- Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer 2013;119:3710-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. The Relationship of Health Insurance and Mortality: Is Lack of Insurance Deadly? Ann Intern Med 2017;167:424-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamel MH, Elfaramawi M, Jadhav S, et al. Insurance Status and Differences in Treatment and Survival of Testicular Cancer Patients. Urology 2016;87:140-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amini A, Rusthoven CG, Waxweiler TV, et al. Association of health insurance with outcomes in adults ages 18 to 64 years with melanoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;74:309-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parikh AA, Robinson J, Zaydfudim VM, et al. The effect of health insurance status on the treatment and outcomes of patients with colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2014;110:227-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen Z, Gao W, Pu L, et al. Impact of insurance status on the survival of gallbladder cancer patients. Oncotarget 2017;8:51663-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams PF, Barnes PM. Summary health statistics for the U.S. population: National Health Interview Survey, 2004. Vital Health Stat 10 2006.1-104. [PubMed]

- Adams PF, Kirzinger WK, Martinez M. Summary health statistics for the U.S. population: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. Vital Health Stat 10 2013.1-95. [PubMed]

- Geynisman DM, Hu JC, Liu L, et al. Treatment patterns and costs for metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients with private insurance in the United States. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2015;13:e93-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang SL, Zhang ZY, Liu ZJ, et al. A real-world study of socioeconomic factors with survival in adults aged 18-64 years with renal cell carcinoma. Future Oncol 2019;15:2503-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lang H, Lindner V, de Fromont M, et al. Multicenter determination of optimal interobserver agreement using the Fuhrman grading system for renal cell carcinoma: Assessment of 241 patients with > 15-year follow-up. Cancer 2005;103:625-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leibovich BC, Lohse CM, Crispen PL, et al. Histological subtype is an independent predictor of outcome for patients with renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 2010;183:1309-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trpkov K, Siadat F. Immunohistochemical screening for the diagnosis of succinate dehydrogenase-deficient renal cell carcinoma and fumarate hydratase-deficient renal cell carcinoma. Ann Transl Med 2019;7:S324. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Canfield S, et al. EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: 2014 update. Eur Urol 2015;67:913-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lagergren J, Andersson G, Talback M, et al. Marital status, education, and income in relation to the risk of esophageal and gastric cancer by histological type and site. Cancer 2016;122:207-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hellenthal NJ, Chamie K, Ramirez ML, et al. Sociodemographic factors associated with nephrectomy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 2009;181:1013-8; discussion 1018-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torbrand C, Wigertz A, Drevin L, et al. Socioeconomic factors and penile cancer risk and mortality; a population-based study. BJU Int 2017;119:254-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Zhu MX, Qi SH. Marital status and survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e0385. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levy AR, Bruen BK, Ku L. Health care reform and women's insurance coverage for breast and cervical cancer screening. Prev Chronic Dis 2012;9:E159. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu LT, Kouzis AC, Schlenger WE. Substance use, dependence, and service utilization among the US uninsured nonelderly population. Am J Public Health 2003;93:2079-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, et al. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer 2003;97:1528-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boevers E, McDowell BD, Mott SL, et al. Insurance Status Is Related to Receipt of Therapy and Survival in Patients with Early-Stage Pancreatic Exocrine Carcinoma. J Cancer Epidemiol 2017;2017:4354592. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rong X, Yang W, Garzon-Muvdi T, et al. Influence of insurance status on survival of adults with glioblastoma multiforme: A population-based study. Cancer 2016;122:3157-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perry AM, Brunner AM, Zou T, et al. Association between insurance status at diagnosis and overall survival in chronic myeloid leukemia: A population-based study. Cancer 2017;123:2561-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Halpern MT, Ward EM, Pavluck AL, et al. Association of insurance status and ethnicity with cancer stage at diagnosis for 12 cancer sites: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:222-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, et al. Unmet Health Needs of Uninsured Adults in the United States. JAMA 2000;284:2061-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berk ML, Schur CL. Access to care: how much difference does Medicaid make? Health Aff (Millwood) 1998;17:169-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Potosky AL, Breen N, Graubard BI, et al. Ellen Parsons. The Association between Health Care Coverage and the Use of Cancer Screening Tests: Results from the 1992 National Health Interview Survey. Med Care 1998;36:257-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Virnig BA. Associating insurance status with cancer stage at diagnosis. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:189-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Daemmrich A, Mohanty A. Healthcare reform in the United States and China: pharmaceutical market implications. J Pharm Policy Pract 2014;7:9. [Crossref] [PubMed]