Sexual function and male cancer

Introduction

Despite the decrease in overall cancer incidence and mortality rates in developed countries since the early 1990s, cancer remains a major public health problem (1). Patient’s quality of life, including sexual functioning, plays in recent years a more significant role in decision making about treatment type. With the introduction of sildenafil (Viagra®) in the late 1990s, media attention towards erectile dysfunction (ED) has made sexual problems more normative and has increased acceptance of help-seeking (2). The most practical and quickest way to evaluate sexual function is by using a questionnaire such as the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) (3) or the shortened IIEF-5 questionnaire (also known as the Sexual Health Inventory for Men or SHIM) (4). The IIEF has been translated and validated in several countries, but it has not been specifically developed for cancer patients. A clear definition of potency is mandatory in order to make meaningful comparisons of the different studies. The 3rd International Consultation on Sexual Dysfunctions defined ED as the consistent or recurrent inability to attain and/or maintain a penile erection sufficient for sexual performance (5).

This manuscript focuses mainly on radiation treatment of the most common male cancers and the sequelae on sexual functioning.

Erectile dysfunction and prostate cancer

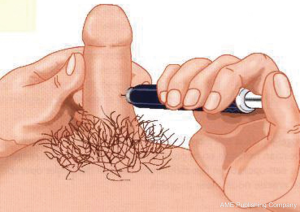

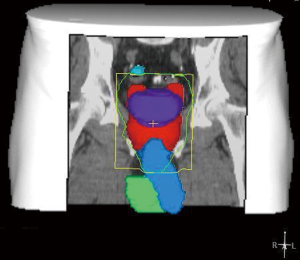

In recent years, the number of patients diagnosed with prostate cancer has increased dramatically because of the widespread use of prostate specific antigen testing and the possibility for cure of early disease. Standard treatments are surgery, external-beam radiotherapy (EBRT), brachytherapy, hormonal therapy or observation. Extensive and critical reviews on post-radiation ED in prostate cancer patients have been published previously (6-8). A study by Zelefsky and Eid concluded that the predominant etiology of radiation-induced impotence was arteriogenic (9). Several, more recent, clinical studies investigated the relationship between the radiation dose to the neurovascular bundels, the penile bulb and the penile bodies (Figure 1) and post-radiation ED (10-26), presenting contradictory results. Most studies have only analyzed small numbers of patients and statistical power should be questioned. Post-radiation ED has more likely a multi-factorial etiology, and is not only based on the radiation dose to one single anatomical structure.

Prospective studies, using validated questionnaires and a proper definition of potency, report post-radiation ED in 60-70% of the patients (27-34). Two more recent prospective trials have shown an incidence of ED in 30-40% of the patients, between one and two years after EBRT (33,34). Brachytherapy was originally introduced not only to limit the detrimental effects of EBRT on bowel and urinary function, but also to help preserve sexual function. After permanent seed implantations, ED rates have ranged from 5-51%, with the highest percentages found after the combination brachytherapy and EBRT (35-45). The highest ED rates, up to 89%, have been reported combining the temporary Iridium-192 implants with EBRT (35,38,40,44).

Erectile dysfunction and bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer in men. If the tumor does not spread beyond the bladder mucosa (superficial bladder cancer) it is treated with resection and adjuvant intravesical chemotherapy or immunotherapy. The optimal treatment for male patients with invasive bladder cancer is surgery (cystoprostatectomy). In some patients, radiotherapy might be the first treatment choice depending on the patient’s age, condition, and comorbidities. Radical cystectomy is associated with changes in the patient’s physiological and psychological well-being. Although radiotherapy preserves the bladder, its function is commonly altered due to urinary frequency and urgency. In a retrospective study of 18 patients (56-75, median 70 years old) treated with EBRT, 13 (72%) recalled being sexually active and having good erections before treatment (46). Of these, only six patients (56%) were active after treatment; three had ED and four reported a decrease in the quality of their erections. In a more recent and controlled study, higher percentages of ED were reported (87% after radiotherapy versus 52% of the men in the control group) (47). Cystectomy and bladder substitution also have significant effects of sexual function. These procedures resulted in ED in 84% of the patients; 63% reported abnormal orgasm and 48% diminished sexual drive (48). In another study, Bjerre and colleagues reported on 76 patients, 27 of whom underwent an ileal conduit diversion and 49 a bladder substitution (49). Preoperatively 82% had normal erections whereas postoperatively, only 9% did. Postoperatively, 38% achieved normal orgasm and 26% were sexually active with intercourse. There was no statistically significant difference between those treated through ileal conduit diversion vs. those treated with bladder substitution.

Erectile dysfunction and penile cancer

Carcinoma of the penis (Figure 2) is a rare malignancy, and accounts for less than 1% of all male cancers in Western countries. Although it is a disease of older men, it is not unusual in younger men (50). The conventional treatment for this cancer is partial or total penile amputation, or radiation. Radiation therapy provides good results in superficially infiltrating tumors, although it may have negative cosmetic and functional effects, often resulting in psychosexual dysfunction (51). Opjordsmoen and colleagues reported on the sexual function of 30 patients after different treatment modalities for low stage penile carcinoma (52). Using a global score for overall sexual functioning based on sexual interest, ability, enjoyment and satisfaction, identity, and frequency of intercourse, they reported that patients after a penectomy had lower scores than patients after either radiation or local surgery. Patients who had undergone only partial penectomy were also dissatisfied and, interestingly, did not function sexually substantially better than patients after total penectomy (52). Windhal and associates retrospectively reported on 67 patients treated with laser beam therapy (51). 87% of the participating patients reported being sexually active; 72% had no ED, 22% had a decrease in sexual function and 50% were satisfied with their sexual life. It appears that most patients with penile carcinoma can still enjoy a sexual life if they can be treated by laser beams (51).

Erectile dysfunction and testicular cancer

Germ cell tumors of the testis are relatively rare and account for about 1% of all male cancers, although the reported incidence appears to be increasing over the last two decades (53,54). Testicular malignancies can be classified histopathologically into seminomas, nonseminomas, and combined tumors. Following a diagnostic orchiectomy, most seminomas are often treated by radiotherapy to the para-aortic lymph nodes and most metastatic non-seminomas by platinum-based chemotherapy. About one third of the non-seminoma patients undergo retroperitoneal lymph nodes dissection (RPLND) that can affect ejaculatory function. The long-term survival for early disease detection approaches 100%. Since most patients undergo treatment during the most sexually active period of their life, the impact of therapy on the quality of life in general, and on sexual functioning, fertility, and body image in particular, is very important. Self-report measures of sexual function conducted soon after treatment indicate high levels of dysfunction that tend to improve over time, in general 3-6 months after treatment (55). Following radiotherapy, deterioration in sexual functioning has been reported in between 1-25% of the patients treated for testicular cancer (56-62). A decrease in sexual desire, in orgasm, and volume of semen was negatively correlated with age (56). Significantly more ED occurred in patients treated for testicular cancer than in healthy controls, and sexual drive was significantly reduced in one study (62). Ejaculatory function worsened in all studies where a non nerve-sparing RPLND was performed.

As a result of careful anatomical studies, the technique of the RPLND has now been modified to include a nerve sparing procedure so that antegrade ejaculation is now maintained in most patients (55). Polychemotherapy induces loss of libido, decreased arousal, and potentially decreased erectile function in patients with testicular cancer (63). Chemotherapy has a major effect on the hormonal, vascular, and nervous systems, all important for normal sexual functioning. In more than half of testicular cancer survivors, Leydig cell dysfunction occurs, as indicated by low plasma testosterone and elevated luteinizing hormone levels (63). Decreased amount of semen is also reported significantly more often by chemotherapy-treated patients than those simply under observation, possibly caused by lower testosterone levels.

Given the potential deforming effects of treatment for testicle removal, several studies have addressed issues of body image following treatment of testicular cancer (58,60,64). More than half of testicular cancer patients reported that their body image had changed after orchiectomy and radiotherapy (65). Yet only about half of the patients reported being informed by their urologist about the availability of testicular implants (60,64) (Figure 3). As expected, body image has been reported to improve after implantation of a testicular prosthesis (64-67).

In conclusion, controlled studies indicate that sexual dysfunction persists for about 2 years post-treatment in testicular cancer patients and may be due to a combination of biological and psychological factors.

Erectile dysfunction and colorectal cancer

Rates of ED after surgery for rectal cancer vary from 0-73% and ejaculation disorders have been reported in up to 59%. The main cause of sexual dysfunction after proctectomy appears to be injury to the autonomic nerves in the pelvis and along the distal aorta and anterior surface of the rectum. Dysfunction is more common after abdominoperineal resection than after low anterior resection. Radiation therapy has become an important part of the multimodality treatment of locally advanced rectal carcinomas. The addition of pre-operative radiation appears to increase the percentage of patients complaining of sexual dysfunction, in both males and females (68,69). Total mesorectal excision (TME) and autonomic nerve preservation spare sexual functioning in patients with rectal cancer, at least in the patients without preoperative radiotherapy (70,71). Sexual dysfunction may be due to a direct effect of radiotherapy or to the more difficult surgical procedure to visualize the autonomic nerves in the irradiated area (68). A multicenter study has shown that even with a careful nerve-preservation technique, men reported impotence or were permanently unable to ejaculate (72).

Ejaculatory and other sexual dysfunctions

A deterioration of sexual activity has been associated with the severity of ejaculatory dysfunction, particularly a decrease in volume or an absence of semen (73). After radiotherapy for prostate cancer, ejaculatory disturbances vary from a reduction or absence of ejaculate volume (2-56%) to discomfort during ejaculation (3-26%) and haemospermia (5-15%). Dissatisfaction with sex life was reported in 25-60%, decreased libido in 8-53%, and decreased sexual desire in 12-58%. One study reported a decreased intensity of orgasm, decreased frequency and rigidity of erections, and decreased importance of sex (9,10,44,45).

Therapy of erectile dysfunction

Prior to the introduction of sildenafil, only one small study reported on the efficacy of intracavernosal injections (ICI; Figure 4) in the treatment of ED after radiotherapy for prostate cancer (74). Dubocq et al. reported a high satisfaction rate and low morbidity in 34 patients who received a penile implant after being irradiated for prostate cancer (75). With the availability of oral drugs to treat ED, these methods of therapy are loosing popularity. The efficacy of sildenafil after radiotherapy for prostate cancer in open-label studies has been reported in up to 90% of the patients (76-80). In one randomized, double-blind trial, sildenafil improved erections significantly as compared to placebo; 55% of the patients had successful intercourse with sildenafil (81,82). Similar results have been reported in the only one randomized, double-blind trial published so far using tadalafil (83,84). Tadalafil once-daily shows similar efficacy, and even better compliance than on-demand (85). In patients treated by both radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy sildenafil seems to be less effective (86).

Conclusions

Quality of life in general and sexual functioning in particular have become very important in cancer patients. Due to modern surgical techniques, improved quality of chemotherapy drugs and advanced radiation techniques, more patients can be successfully treated though still many patients complain of impaired sexual function. It is important to standardize procedures to assess quality of life in cancer patients and to use validated questionnaires. Collecting data on an ongoing basis before and long after treatment is mandatory, and control groups must be used. Patients should be offered sexual counselling and informed about the availability of effective treatments for sexual dysfunction. Sexuality in general, and in relation to cancer in particular, should be an integral part of training at the undergraduate and postgraduate level. This does not happen in most medical schools and training programs in most countries around the world. Cancer clinics may offer advantages when a specific consultation for sexual function and dysfunction in cancer patients is arranged. The great majority of oncology professionals are scared to address sexuality and the great majority of sexological professionals are scared by cancer (87). It is time that cancer specialists and sexologists better understand each other. Cancer affects quantity and quality of life. The challenge for any health care professional is to address both components with compassion. The 3rd International Consultation on Sexual Medicine appointed for the first time in 2009 a Committee on chronic illness (including cancer) and sexual medicine (5). The recommendations of the committee are very useful to help developing research programs in oncology and sexual medicine (88).

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;62:220-41. [PubMed]

- Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the context of help-seeking. Am Psychol 2003;58:5-14. [PubMed]

- Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, et al. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF). A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 1997;49:822-30. [PubMed]

- Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, et al. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 1999;11:319-26. [PubMed]

- Montorsi F, Adaikan G, Becher E, et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in men. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3572-88. [PubMed]

- Incrocci L, Slob AK, Levendag PC. Sexual (dys)function after radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;52:681-93. [PubMed]

- Incrocci L, Slob AK. Incidence, etiology, and therapy for erectile dysfunction after external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Urology 2002;60:1-7. [PubMed]

- Incrocci L. Sexual function after external-beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer: What do we know? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2006;57:165-73. [PubMed]

- Zelefsky MJ, Eid JF. Elucidating the etiology of erectile dysfunction after definitive therapy for prostatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998;40:129-33. [PubMed]

- DiBiase SJ, Wallner K, Tralins K, et al. Brachytherapy radiation doses to the neurovascular bundles. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;46:1301-7. [PubMed]

- Merrick GS, Butler WM, Dorsey AT, et al. A comparison of radiation dose to the neurovascular bundles in men with and without prostate brachytherapy-induced erectile dysfunction. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;48:1069-74. [PubMed]

- Merrick GS, Wallner K, Butler WM, et al. A comparison of radiation dose to the bulb of the penis in men with and without prostate brachytherapy-induced erectile dysfunction. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001;50:597-604. [PubMed]

- Merrick GS, Butler WM, Wallner KE, et al. The importance of radiation doses to the penile bulb vs. crura in the development of postbrachytherapy erectile dysfunction. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;54:1055-62. [PubMed]

- Merrick GS, Butler WM, Wallner KE, et al. Erectile function after prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;62:437-47. [PubMed]

- Fisch BM, Pickett B, Weinberg V, et al. Dose of radiation received by the bulb of the penis correlates with risk of impotence after three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Urology 2001;57:955-9. [PubMed]

- Kiteley RA, Lee WR, deGuzman AF, et al. Radiation dose to the neurovascular bundles or penile bulb does not predict erectile dysfunction after prostate brachytherapy. Brachytherapy 2002;1:90-4. [PubMed]

- Selek U, Cheung R, Lii M, et al. Erectile dysfunction and radiation dose to penile base structures: a lack of correlation. In J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;59:1039-46.

- Roach M, Winter K, Michalski JM, et al. Penile bulb dose and impotence after three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer on RTOG 9406: findings from a prospective, multi-institutional, phase I/II dose-escalation study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;60:1351-6. [PubMed]

- Wernicke AG, Valicenti R, Dieva K, et al. Radiation dose delivered to the proximal penis as a predictor of the risk of erectile dysfunction after three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;60:1357-63. [PubMed]

- Wright JL, Newhouse JH, Laguna JL, et al. Localization of neurovascular bundles on pelvic CT and evaluation of radiation dose to structures putatively involved in erectile dysfunction after prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;59:426-35. [PubMed]

- Macdonald AG, Keyes M, Kruk A, et al. Predictive factors for erectile dysfunction in men with prostate cancer after brachytherapy: is dose to the penile bulb important? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;63:155-63. [PubMed]

- Mangar SA, Sydes MR, Tucker HL, et al. Evaluating the relationship between erectile dysfunction and dose received by the penile bulb: using data from a randomised controlled trial of conformal radiotherapy in prostate cancer (MRC RT01, ISRCTN47772397). Radiother Oncol 2006;80:355-62. [PubMed]

- Brown MW, Brooks JP, Albert PS, et al. An analysis of erectile function after intensity modulated radiation therapy for localized prostate carcinoma. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2007;10:189-93. [PubMed]

- van der Wielen GJ, Hoogeman MS, Dohle GR, et al. Dose-volume parameters of the corpora cavernosa do not correlate with erectile dysfunction after external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer: results from a dose-escalation trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;71:795-800. [PubMed]

- Solan AN, Cesaretti JA, Stone NN, et al. There is no correlation between erectile dysfunction and dose to penile bulb and neurovascular bundles following real-time low-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;73:1468-74. [PubMed]

- van der Wielen GJ, Mulhall JP, Incrocci L. Erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy for prostate cancer and radiation dose to the penile structures: A critical review. Radiother Oncol 2007;84:107-13. [PubMed]

- Incrocci L. Brachytherapy of prostate cancer and sexual dysfunction. UroOncology 2002;2:107-12.

- Pilepich MV, Krall JM, Al-Sarraf M, et al. Androgen deprivation with radiation therapy compared with radiation therapy alone for locally advanced prostatic carcinoma: a randomized comparative trial of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Urology 1995;45:616-23. [PubMed]

- Beckendorf V, Hay M, Rozan R, et al. Changes in sexual function after radiotherapy treatment of prostate cancer. Br J Urol 1996;77:118-23. [PubMed]

- Beard CJ, Propert KJ, Rieker PP, et al. Complications after treatment with external-beam irradiation in early-stage prostate cancer patients: a prospective multiinstitutional outcomes study. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:223-9. [PubMed]

- Borghede G, Hedelin H. Radiotherapy of localised prostate cancer. Analysis of late treatment complications. A prospective study. Radiother Oncol 1997;43:139-46. [PubMed]

- Turner SL, Adams K, Bull CA, et al. Sexual dysfunction after radical radiation therapy for prostate cancer: a prospective evaluation. Urology 1999;54:124-9. [PubMed]

- van der Wielen GJ, van Putten WLJ, Incrocci L. Sexual Function After Three-Dimensional Conformal Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer: Results from a dose-escalation trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007;68:479-84. [PubMed]

- Pinkawa M, Gagel B, Piroth MD, et al. Erectile dysfunction after external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2009;55:227-34. [PubMed]

- Martinez A, Gonzalez J, Stromberg J, et al. Conformal prostate brachytherapy: initial experience of a phase I/II dose-escalating trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995;33:1019-27. [PubMed]

- Arterbery VE, Frazier A, Dalmia P, et al. Quality of life after permanent prostate implant. Semin Surg Oncol 1997;13:461-4. [PubMed]

- Koutrouvelis PG. Three-dimensional stereotactic posterior ischiorectal space computerized tomography guided brachytherapy of prostate cancer: a preliminary report. J Urol 1998;159:142-5. [PubMed]

- Joly F, Brune D, Couette JE, et al. Health-related quality of life and sequelae in patients treated with brachytherapy and external beam irradiation for localized prostate cancer. Ann Oncol 1998;9:751-7. [PubMed]

- Sharkey J, Chovnick SD, Behar RJ, et al. Outpatient ultrasound-guided Palladium-103 brachytherapy for localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a preliminary report of 434 patients. Urology 1998;51:796-803. [PubMed]

- Kestin LL, Martinez AA, Stromberg JS, et al. Matched-pair analysis of conformal high-dose-rate brachytherapy boost versus external-beam radiation therapy alone for locally advanced prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2869-80. [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Ortiz RF, Broderick GA, Rovner ES, et al. Erectile function and quality of life after interstitial radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Impot Res 2000;12:S18-24. [PubMed]

- Sharkey J, Chovnick SD, Behar RJ, et al. Minimally invasive treatment for localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: review of 1048 patients treated with ultrasound-guided Palladium-103 brachytherapy. J Endourol 2000;14:343-50. [PubMed]

- Zelefsky MJ, Hollister T, Raben A, et al. Five-year biochemical outcome and toxicity with transperineal CT-planned permanent I-125 prostate implantation for patients with localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;47:1261-6. [PubMed]

- Potters L, Torre T, Fearn PA, et al. Potency after permanent prostate brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001;50:1235-42. [PubMed]

- Stock RG, Kao J, Stone NN. Penile erectile function after permanent radioactive seed implantation for treatment of prostate cancer. J Urol 2001;165:436-9. [PubMed]

- Little FA, Howard GC. Sexual function following radical radiotherapy for bladder cancer. Radiother Oncol 1998;49:157-61. [PubMed]

- Fokdal L, Høyer M, Meldgaard P, et al. Long-term bladder, colorectal, and sexual functions after radical radiotherapy for urinary bladder cancer. Radiother Oncol 2004;72:139-45. [PubMed]

- Månsson A, Caruso A, Capovilla E, et al. Quality of life after radical cystectomy and orthotopic bladder substitution: A comparison between Italian and Swedish men. BJU Int 2000;85:26-31. [PubMed]

- Bjerre BD, Johansen C, Steven K. Sexological problems after cystectomy: bladder substitution compared with ileal conduit diversion. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1998;32:187-93. [PubMed]

- Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC. Penile carcinoma: a challenge for the developing world. Lancet Oncol 2004;5:240-7. [PubMed]

- Windahl T, Skeppner E, Andersson SO, et al. Sexual function and satisfaction in men after laser treatment for penile carcinoma. J Urol 2004;172:648-51. [PubMed]

- Opjordsmoen S, Wahere H, Aass N, et al. Sexuality in patients treated for penile cancer: Patients’ experience and doctors’ judgment. Br J Urol 1994;73:554-60. [PubMed]

- Che M, Tamboli P, Ro J, et al. Bilateral testicular germ cell tumours: Twenty-year experience at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Cancer 2002;95:1228-33. [PubMed]

- Huyghe E, Matsuda T, Thonneau P. Increasing incidence of testicular cancer worldwide: a review. J Urol 2003;170:5-11. [PubMed]

- van Basten JP, Schrafford Koops H, Sleijfer DT, et al. Current concepts about testicular cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 1997;23:354-60. [PubMed]

- Schover LR, Gonzales M, von Eschenbach AC. Sexual and marital relationships after radiotherapy for seminoma. Urology 1986;27:117-23. [PubMed]

- Jonker-Pool G, van Basten JP, Hoekstra HJ, et al. Sexual functioning after treatment for testicular cancer. Cancer 1997;80:454-64. [PubMed]

- Tinkler SD, Howard GC, Kerr GR. Sexual morbidity following radiotherapy for germ cell tumors of the testis. Radiother Oncol 1992;25:207-12. [PubMed]

- Caffo O, Amichetti M. Evaluation of sexual life after orchidectomy followed by radiotherapy for early-stage seminoma of the testis. BJU Int 1999;83:462-8. [PubMed]

- Incrocci L, Hop WC, Wijnmaalen A, et al. Treatment outcome, body image, and sexual functioning after orchiectomy and radiotherapy for stage I-II testicular seminoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;53:1165-73. [PubMed]

- Arai Y, Kawakita M, Okada Y, et al. Sexuality and fertility in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:1444-8. [PubMed]

- Nazareth I, Lewin J, King M. Sexual dysfunction after treatment for testicular cancer. A systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2001;51:735-43. [PubMed]

- van Basten JP, Jonker-Pool G, van Driel MF, et al. Sexual functioning after multimodality treatment for disseminated nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumor. J Urol 1997;158:1411-6. [PubMed]

- Gritz ER, Wellisch DK, Wang HJ, et al. Long-term effects of testicular cancer on sexual functioning in married couples. Cancer 1989;64:1560-7. [PubMed]

- Incrocci L, Bosch JL, Slob AK. Testicular prostheses: body image and sexual functioning. BJU Int 1999;84:1043-5. [PubMed]

- Adshead J, Khoubehi B, Wood J, et al. Testicular implants and patient satisfaction: a questionnaire-based study of men after orchidectomy for testicular cancer. BJU Int 2001;88:559-62. [PubMed]

- Lynch MJ, Pryor JP. Testicular prostheses: the patient's perception. Br J Urol 1992;70:420-2. [PubMed]

- Bonnel C, Parc YR, Pocard M, et al. Effects of preoperative radiotherapy for primary resectable rectal adenocarcinoma on male sexual and urinary function. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45:934-9. [PubMed]

- Marijnen CA, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, et al. Impact of short-term preoperative radiotherapy on health-related quality of life and sexual functioning in primary rectal cancer. Report of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:1847-58. [PubMed]

- Nesbakken A, Nygaard K, Bull-Njaa T, et al. Bladder and sexual dysfunction after mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2000;87:206-10. [PubMed]

- Pocard M, Zinzindohoue F, Haab F, et al. A prospective study of sexual and urinary function before and after total mesorectal excision with autonomic nerve preservation for rectal cancer. Surgery 2002;131:368-72. [PubMed]

- Maas CP, Moriya Y, Steup WH, et al. Radical and nerve-preserving surgery for rectal cancer in The Netherlands: a prospective study on morbidity and functional outcome. Br J Surg 1998;85:92-7. [PubMed]

- Arai Y, Aoki Y, Okubo K, et al. Impact of interventional therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia on quality of life and sexual function: a prospective study. J Urol 2000;164:1206-11. [PubMed]

- Pierce LJ, Whittington R, Hanno PM, et al. Pharmacologic erection with intracavernosal injection for men with sexual dysfunction following irradiation: a preliminary report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991;21:1311-4. [PubMed]

- Dubocq FM, Bianco FJ Jr, Maralani SJ, et al. Outcome analysis of penile implant surgery after external beam radiation for prostate cancer. J Urol 1997;158:1787-90. [PubMed]

- Zelefsky MJ, McKee AB, Lee H, et al. Efficacy of oral sildenafil in patients with erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy for carcinoma of the prostate. Urology 1999;53:775-8. [PubMed]

- Kedia S, Zippe CD, Agarwal A, et al. Treatment of erectile dysfunction with sildenafil citrate (Viagra) after radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Urology 1999;54:308-12. [PubMed]

- Valicenti RK, Choi E, Chen C, et al. Sildenafil citrate effectively reverses sexual dysfunction induced by three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy. Urology 2001;57:769-73. [PubMed]

- Weber DC, Bieri S, Kurtz JM, et al. Prospective pilot study of sildenafil for treatment of postradiotherapy erectile dysfunction in patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:3444-9. [PubMed]

- Ohebshalom M, Parker M, Guhring P, et al. The efficacy of sildenafil citrate following radiation therapy for prostate cancer: temporal considerations. J Urol 2005;174:258-62. [PubMed]

- Incrocci L, Koper PC, Hop WC, et al. Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) and erectile dysfunction following external-beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001;51:1190-5. [PubMed]

- Incrocci L, Hop WC, Slob AK. Efficacy of sildenafil in an open-label study as a continuation of a double-blind study in the treatment of erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy of prostate cancer. Urology 2003;62:116-20. [PubMed]

- Incrocci L, Slagter C, Slob AK, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study to assess the efficacy of tadalafil (Cialis) in the treatment of erectile dysfunction following three-dimensional conformal external-beam radiotherapy for prostatic carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;66:439-44. [PubMed]

- Incrocci L, Slob AK, Hop WC. Tadalafil (Cialis) and erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy for prostate cancer: an open-label extension of a blinded trial. Urology 2007;70:1190-3. [PubMed]

- Ricardi U, Gontero P, Ciammella P, et al. Efficacy and safety of tadalafil 20 mg on demand vs. tadalafil 5 mg once-a-day in the treatment of post-radiotherapy erectile dysfunction in prostate cancer men: a randomized phase II trial. J Sex Med 2010;7:2851-9. [PubMed]

- Watkins Bruner D, James JL, Bryan CJ, et al. Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover trial of treating erectile dysfunction with sildenafil after radiotherapy and short-term androgen deprivation therapy: results of RTOG 0215. J Sex Med 2011;8:1228-38. [PubMed]

- Incrocci L. Talking about sex to oncologists and cancer to sexologists. J Sex Med 2011;8:3251-3. [PubMed]

- Sadovsky R, Basson R, Krychman M, et al. Cancer and sexual problems. J Sex Med 2010;7:349-73. [PubMed]