The pathophysiology of acquired premature ejaculation

In 1943, Shapiro (1) proposed classification of premature ejaculation (PE) into two types, types B and A. In 1989, Godpodinoff (2) renamed both types as lifelong (primary) and acquired (secondary) PE. Lifelong PE is a syndrome characterized by a cluster of core symptoms including early ejaculation at nearly every intercourse within 30–60 seconds in the majority of cases (80%) or between 1–2 minutes (20%), with every or nearly every sexual partner and from the first sexual encounters onwards (3,4). Acquired PE differs in that sufferers develop early ejaculation at some point in their life, which is often situational, having previously had normal ejaculation experiences. The main distinguishing features between presentations of these two syndromes are the time of onset of symptoms and the reduction in previously normal ejaculatory latency of acquired PE (5,6).

Community based normative intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT) research and observational studies of men with PE demonstrated that although IELTs of less than 1 minute have a low prevalence of about 2.5% in the general population, a substantially higher percentage of men with normal IELT complain of PE (7-9). Waldinger and Schweitzer (10,11) explained this diversity with a new classification of PE in which four PE subtypes are distinguished on the basis of the duration of the IELT, frequency of complaints, and course in life. This classification includes natural variable PE (or variable PE) and premature-like ejaculatory dysfunction (or subjective PE) in addition to lifelong PE and acquired PE. Men with variable PE occasionally experience an early ejaculation. It should not be regarded as a disorder, but as a natural variation of the ejaculation time in men (12). Men with subjective PE complain of PE, while actually having a normal or even extended ejaculation time (12). The complaint of PE in these men is probably related to psychological and/or cultural factors. In contrast, the consistent early ejaculations of lifelong PE suggested an underlying neurobiological functional disturbance, whereas the early ejaculation of acquired PE is more related to underlying medical causes.

Serefoglu et al. (13,14) confirmed the existence of these four PE subtypes in a cohort of men in Turkey. Recently, Zhang et al. (15) and Gao et al. (16) using a similar methodology confirmed similar prevalence rates of the four PE subtypes in China to that reported by Serefoglu et al. (13,14). This new classification and continued research into the diverse phenomenology, etiology and pathogenesis of PE is expected to provide a better understanding of the four PE subtypes (10). Although the pathogenesis of lifelong and acquired PE differs, both share the dimensions of a lack of ejaculatory control and the presence of negative personal consequences.

Definition of acquired PE

Research into the treatment and epidemiology of PE is heavily dependent on how PE is defined. The medical literature contains several univariate and multivariate operational definitions of PE (5,6,17-26). Each of these definitions characterise men with PE using all or most of the accepted dimensions of this condition: ejaculatory latency, perceived ability to control ejaculation, reduced sexual satisfaction, personal distress, partner distress and interpersonal or relationship distress. None of these defintions was supported by evidence-based clinical research.

In the last decade, substantial progress has been made in the development of evidence-based methodology for PE epidemiologic and drug treatment research using the objective IELT and subjective validated patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures. In October 2007, the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) convened an initial meeting of the first Ad Hoc ISSM Committee for the Definition of Premature Ejaculation to develop the first contemporary, evidence-based definition of lifelong PE (4). The committee was, however, unable to identify sufficient published objective data to craft an evidence-based definition of acquired PE. The committee anticipated that future studies would generate sufficient data to develop an evidence-based definition for acquired PE.

In April 2013, the ISSM convened a second Ad Hoc ISSM Committee for the Definition of Premature Ejaculation in Bangalore, India. The brief of the committee was to evaluate the current published data and attempt to develop a contemporary, evidence-based definition of acquired PE and/or a single unifying definition of both acquired and lifelong PE. Members unanimously agreed that although lifelong and acquired PE are distinct and different demographic and etiological populations, they can be jointly defined, in part, by the constructs of time from penetration to ejaculation, inability to delay ejaculation and negative personal consequences from PE. The committee agreed that the presence of these mutual constructs was sufficient justification for the development of a single unifying definition of both lifelong and acquired PE. Finally, the committee determined that the presence of a a clinically significant and bothersome reduction in latency time, often to about 3 minutes or less was an additional key defining dimension of acquired PE.

The second Ad Hoc ISSM Committee for the Definition of Premature Ejaculation [2013] defined PE (lifelong and acquired PE) as a male sexual dysfunction characterized by:

- Ejaculation which always or nearly always occurs prior to or within about 1 minute of vaginal penetration (lifelong PE), or, a clinically significant and bothersome reduction in latency time, often to about 3 minutes or less (acquired PE);

- The inability to delay ejaculation on all or nearly all vaginal penetrations;

- Negative personal consequences, such as distress, bother, frustration and/or the avoidance of sexual intimacy (6).

The unified ISSM definition of lifelong and acquired PE represents the first evidence-based definition for these conditions. This definition should form the basis for the office diagnosis of PE and the design of PE observational and interventional clinical trials. It is limited to men engaging in vaginal intercourse as there are few studies available on PE research in homosexual men or during other forms of sexual expression. This definition intentionally includes a degree of diagnostic conservatism and flexibility. The 1 minute IELT cut-off point for lifelong PE should not be applied in the most absolute sense, as about 10% of men seeking treatment for lifelong PE have IELTs of 1–2 minutes. The phrase, “within about 1 minute” must be interpreted as giving the clinician sufficient flexibility to diagnose PE also in men who report an IELT as long as 90 seconds. Similarly, a degree of flexible clinical judgement is key to the recognition and interpretation of a bothersome change in ejaculatory latency with reduction of pre-morbid latency to ≤3 minutes in men with acquired PE. Men who report these ejaculatory latencies but describe adequate control and no personal negative consequences related to their rapid ejaculation do not merit the diagnosis of PE.

American Psychiatric Association has recently published Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) and they defined PE as “A persistent or recurrent pattern of ejaculation occurring during partnered sexual activity within approximately 1 minute following vaginal penetration and before the individual wishes it” (26). This must have been present for at least 6 months and must be experienced on almost all or all (approximately 75–100%) occasions of sexual activity (in identified situational contexts or, if generalized, in all contexts). In addition, it causes clinically significant distress in the individual and it is not better explained by a nonsexual mental disorder or as a consequence of severe relationship distress or other significant stressors and is not attributable to the effects of a substance/medication or another medical condition”. Although the DSM-5 definition classifies PE as “lifelong” and “acquired”, it does not provide different cut-off IELT values for these conditions. However, the DSM-5 categorizes PE according to the IELT values as follows: (I) mild PE, ejaculation occurs within approximately 30 seconds to 1 minute of vaginal penetration; (II) moderate PE, ejaculation occurs within approximately 15–30 seconds of vaginal penetration, and; (III) severe PE, ejaculation occurs prior to sexual activity, at the start of sexual activity, or within approximately 15 seconds of vaginal penetration.

Prevalence of acquired PE

Reliable information on the prevalence of lifelong and acquired PE in the general male population is lacking. PE has been estimated to occur in 4–39% of men in the general community (27-33), and is often reported as the most common self reported male sexual disorder (34). There is, however, a substantial disparity between the incidence of PE in epidemiological studies which rely upon either patient self-report of PE and/or inconsistent and poorly validated definitions of PE (9,32,35), and that suggested by community based stopwatch studies of the intravaginal ejaculation latency time (IELT), the time interval between penetration and ejaculation (8). The latter demonstrates that the distribution of the IELT is positively skewed, with a median IELT of 5.4 minutes (range, 0.55–44.1 minutes), decreases with age and varies between countries, and supports the notion that IELTs of less than 1 minute are statistically abnormal compared to men in the general western population (8).

Prevalence data derived from patient self report will be appreciably higher than prevalence estimates based on clinician diagnosis utilizing the more conservative ISSM definition of PE. The following studies demonstrate the varying prevalence estimates ranging from 30% down to 3%. Data from The Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors (GSSAB), an international survey investigating the attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, and sexual satisfaction of 27,500 men and women aged 40–80 years, reported the global prevalence of PE (based on subject self-report) to be approximately 30% across all age groups (36,37). Perception of “normal” ejaculatory latency varied by country and differed when assessed either by the patient or their partner (38). A core limitation of the GSSAB survey stems from the fact that the youngest participants were aged 40 years, an age when the incidence of PE might be different from younger males (34). Contrary to the GSSAB study, the Premature Ejaculation Prevalence and Attitude Survey found the prevalence of PE among men aged 18 to 70 to be 22.7% (33). The real prevalence of PE is difficult to assess in clinical practice (34).

Basile Fasolo et al. reported that 2,658 of 12,558 men (21.2%) attending a free andrological consultation self-diagnosed PE, the majority describing acquired PE (14.8%) with 4.5% describing lifelong PE (39). In contrast, Serefoglu et al. (13) reported that the majority of PE treatment-seeking patients described lifelong PE (62.5%) compared to acquired PE (16.1%). Similar findings were reported by Zhang et al. who found that the majority of 1,988 Chinese outpatients described lifelong PE (35.6%) or acquired PE (28.07%). These data provide evidence that lifelong and acquired PE patients comprise the majority of the patients who seek treatment for the complaint of ejaculating prematurely. In addition, there appears to be a disparity between the incidence of the various PE sub-types in the general community and in men actively seeking treatment for PE.

Consistent with this notion, Serefoglu et al. (14) subsequently reported an overall PE prevalence of 19.8% comprising lifelong PE (2.3%), acquired PE (3.9%), variable PE (8.5%) and subjective PE (5.1%). Using similar research methodology, Gao et al. (16) reported that 25.80% of 3,016 Chinese men complained of PE, with similar prevalence of lifelong PE (3.18%), acquired PE (4.84%), variable PE (11.38%) and subjective PE (6.4%). Of particular interest is the report of Serefoglu et al. (14) that men with acquired PE are more likely to seek medical treatment than men with lifelong PE (26.53% vs. 12.77%). This finding was confirmed by Gao et al. who demonstrated that acquired PE patients were more likely to seek (17.12% vs. 14.58%) and plan to seek (36.30% vs. 27.08%) treatment for their complaints compared to men with lifelong PE (16). These data suggest that the prevalence of acquired PE in the community is approximately around 4% among sexually active adults and that these patients are more likely to seek medical treatment.

Aetiology of acquired PE

Historically, attempts to explain the etiology of PE have included a diverse range of biological and psychological theories. Most of these proposed aetiologies are not evidence based and are speculative at best. Although men with lifelong and acquired PE appear to share the dimensions of short ejaculatory latency, reduced or absent perceived ejaculatory control and the presence of negative personal consequences from PE, they remain distinct and different demographic and etiological populations (40).

Acquired PE is commonly due to sexual performance anxiety (41), psychological or relationship problems (41), erectile dysfunction (ED) (36), and occasionally prostatitis (42), hyperthyroidism (43), or during withdrawal/detoxification from prescribed (44) or recreational drugs (45). Consistent with the predominant organic etiology of acquired PE, men with this complaint are usually older, have a higher mean BMI and a greater incidence of comorbid disease including hypertension, sexual desire disorder, diabetes mellitus, chronic prostatitis, and ED compared to lifelong, variable and subjective PE (13-16,39,40,46).

As such, A-PE is best regarded as a psychoneureoendocrine and urological symptom with possible comorbidity with ED and other sexual disturbances. The manifold candidate aetiologies of A-PE are perhaps best regarded as a series of psychological, relational and organic risk factors for A-PE (Table 1).

Full table

Psychological risk factor

Psychological problems such as sexual performance anxiety, psychological or relationship problems may cause acquired PE (41).

Anxiety has been reported as a cause of PE by multiple authors and is entrenched in the folklore of sexual medicine as the most likely cause of PE despite scant empirical research evidence to support any causal role (47-49). It should be noted however that anxiety and depression may also be the effect rather than the cause of PE and several recent studies have confirmed the bi-directional relatiopnship between anxiety, depression and PE (50-54).

Several authors have suggested that anxiety activates the sympathetic nervous system and reduces the ejaculatory threshold as a result of an earlier emission phase of ejaculation (48). The possibility that high levels of anxiety and excessive and controlling concerns about sexual performance and potential sexual failure might distract a man from monitoring his level of arousal and recognising the prodromal sensations that precede ejaculatory inevitability has been suggested as a possible cause of PE by several authors (55-58). The association between PE, anxiety and other psychological disorders has been measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (59). Furthermore, anxiety appears to interact with and exacebrate the somatic and perhaps genetic vulnerability to rapid ejaculation of some men (60).

The causal link between anxiety and PE has been largely regarded as speculative and not supported by any empirical evidence and is in fact contrary to empirical evidence from other researchers. Strassberg et al. [1990] failed to demonstrate any difference in sexual anxiety between a control group of men with normal ejaculatory control and men with PE (60). However, Corona et al. elegantly demonstrated high levels of free floating anxiety in A-PE (61). Consistent with this finding, Rajkumar et al. reported that performance anxiety during intercourse was significantly associated with acquired PE (52). In addition, men with pre-existing anxiety disorders were more likely to experience performance anxiety related to sex, and to have PE without comorbid ED (51). Furthermore, men with subjective PE and a normal ejaculatory latency appear to have a greater psychological burden than men with definition diagnosed PE including depression, low self-esteem, bother, and low sexual satisfaction (54). However, PE appears to be less associated with trait anxiety and depression compared to ED, a finding that corroborates the recent acknowledgement of PE as a more biologically based condition (50).

Sexual behaviour such as PE can also be adversely effected by several other psychological problems and confounding factors. PE has been considered frequent, if not normal, during early sexual experiences. Masters and Johnson suggested that confounding factors such as the risk of unwanted discovery (such as copulating in a car), experiences with prostitutes, and anxiety due to poor sexual education (e.g., absence of adequate knowledge of contraceptive methods) might worsen the poor ejacultory control commonly observed in young men (62). Social phobia can be a tract characterizing both lifelong PE and acquired PE. PE was the most common sexual dysfunction in male social phobic patients (63). PE was highly associated (P=0.015) with social phobia, with an odds ratio of 2.55 (64). Sexual disorders can be the result of distortions of belief and false convictions about sexuality which are established in childhood. Destructive attitudes are usually exerted by parents but also by other power figures within and outside the family (65). Classic psychoanalytic theories have identified varying degrees of sadistic or narcissistic behavior in sufferers of PE (66). Some psychoanalysists identify men who ejaculate prematurely as typically passive and masochistic in their marriage and obsessive-compulsive in character (67). These theories were the basis of Helen Kaplan’s initial premise that PE is the result of an unconscious hatred of women (56,68). By ejaculating quickly, a man symbolically and physically “steals” the woman’s orgasm. However, the same researcher rejected her own theory when she found that men with PE do not have any particular neuroses or personality disorders (56).

Alexithymia is a deficit in identifying and communicating emotions that is presumed to play an important role in psychosomatic diseases. Alexithymic features, and in particular, an externally oriented cognitive style, can be seen as possible risk and/or maintenance factors for PE. Alexithymia could represent a variable to be assessed for an integrated diagnosis and treatment of PE (69).

In conclusion, the etiological approach of psychology to PE in general and to A-PE in particular should be re-thought. Psychological involvement can be either a cause or caused by A-PE.

The sexual dysfunction risk factor

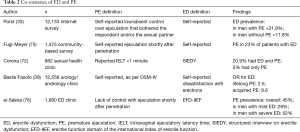

Multiples studies have observed that hypoactive sexual desire, ED, partner female sexual dysfunction (FSD) and PE often coexist (33,36,70-74) (Table 2). Recent data demonstrates that as many as half of subjects with ED also experience PE (33,36,39).

Hypoactive sexual desire may also lead to PE, due to an unconscious desire to abbreviate unwanted penetration (77). Similarly, diminished sexual desire can be a consequence of chronic and frustrating PE. Interesting, low sexual desire may be due to a lack of sexual arousal, such as in ED. PE and low desire, singly or in combination, are, in fact, significantly associated with severe rather than mild ED at presentation (76). Furthermore, FSD including anorgasmia, hypoactive sexual desire, sexual aversion, sexual arousal disorders, and sexual pain disorders such as vaginismus (74) may also be related to acquired PE. Female sexual dysfunction may be secondary to the male PE with or without ED, and can be considered as a frequent complication of this condition. In other cases, PE may be the result of hidden female arousal difficulties (78). Such partner influences emphasize the need to diagnose and treat the couple, not simply the patient (79).

Several large cross sectional observational studies confirm the link between ED and PE (Table 2) (33,36,39,72,75,76). The Premature Ejaculation Prevalence and Attitudes (PEPA) Survey of 12,133 men from three countries found self-reported ED rates of 31.9% and 11.8% in men with and without PE respectively (33). Basile Fasolo et al. reported that ED is more common in men with PE, particularly in men with acquired PE (39). The GSSAB found that men with PE had a country specific odds ratio of 3.7–11.9 of having ED (36). In a nationally representative sample of 1,475 Swedish men, 23% of men reporting erectile difficulties also reported PE (75).

Full table

While these large cross-sectional studies clearly establish the frequent coexistence of the two conditions, they do not provide information about temporality and consequently causality.

In a cohort of 184 men attending a sexual dysfunction clinic, 121 complained of ED, 52 of PE, and 11 of both conditions (24). Interestingly, careful evaluation and administration of the IIEF-5 demonstrated that 24% of patients only complaining of ED actually had experienced PE prior to ED onset. Moreover, antecedent or concurrent ED was identified by the IIEF-5 in 40% of patients complaining of PE only. Patients with ED and PE were initially treated with a type 5 phosphodiesterase (PDE5) inhibitor alone, which resulted in partial or complete resolution of PE in 30%.

Jannini et al. reported a bidirectional relationship between ED and PE where either one can cause/exacerbate the other, potentially creating a vicious cycle (24). Subjects with ED may either require higher levels of stimulation to achieve an erection or intentionally “rush” intercourse to prevent early detumescence of a partial erection, resulting in ejaculation with a brief latency (24). On the other hand, PE can result in ED. Conscious efforts to delay ejaculation by reducing the level of excitation might result in loss of penile erection. Interestingly, various studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of PE is positively associated with ED severity (61,76,80). el-Sakka et al. reported that PE was present in 29.5% of men with mild ED, and 52.4% those with severe ED (76). In addition, high levels of performance anxiety related to ED may serve to only worsen their prematurity. A study of more than 800 men attending an outpatient clinic for sexual problems found that anxiety symptoms, as assessed by a validated questionnaire, were significantly associated with erectile difficulties and PE (81).

Endocrine risk factors

Hormones play a central role in the control of ejaculation (82); this implies that pathological hormonal levels may directly or indirectly affect the ejaculatory control (83).

The role of sex steroids

Low serum testosterone levels have been inconsistently associated with PE (84,85). However, other reports have suggested that hypogonadism can be considered a possible cause of delayed ejaculation (86,87). Testosterone plays a crucial role in male sexual response, acting at both the central and peripheral levels, and is a clear determinant of motivation to seek sexual contact.

Several studies in hypogonadal men have demonstrated that testosterone replacement has an unequivocal role in restoring sexual desire, spontaneous sexual thoughts and attraction to erotic stimuli. The testosterone-dependency of PDE5 expression and activity has also been demonstrated in other portions of the male genital tract such as the vas deferens, a critical effector for semen emission and ejaculation (88,89). Recent data suggests that testosterone plays a facilitatory role in the control of ejaculatory reflex (87). However, Paduch et al. reported that testosterone replacement was not associated with significant improvement in ED in androgen-deficient men (90). Different testosterone levels identify different subsets of ejaculatory disturbance. While a higher testosterone level may characterize PE, delayed ejaculation is associated with hypogonadal levels. Taken together, these data suggest a role for androgens in the mechanism of ejaculation (87).

Both central and peripheral mechanisms have been advocated to explain this association. The first explanation is psychoendocrinal. Testosterone level, in addition to its action on sexual response, profoundly influences male behaviour. High testosterone levels in human adults are associated with leadership, toughness, personal power and aggressive dominance (91). Rowland considers delayed ejaculation to be essentially characterized by the uncoupling of a decreased subjective and a preserved genital reaction in sexual arousal (92). It could thus be speculated that hypogonadism and related reduction in sexual confidence and aggressiveness could play a critical role in the control of ejaculation timing, reducing the internal cues for reaching orgasm and ejaculation. The second hypothesis is neurological. Recent data from animal models seem to support the central action of testosterone in the control of the ejaculation reflex. Keleta et al. (93) demonstrated that long-term testosterone treatment in rats significantly decreased 5-HT in the brain. Another intriguing possibility involves the possible peripheral role of testosterone in regulating male genital tract motility. In rabbit hypogonadism, it was found that PDE5 is less expressed and biologically active in the vas deferens (89). Testosterone administration completely reversed these alterations. Hence, it is possible that hypogonadism-associated delayed ejaculation is due to an increased inhibitory nitrergic tone on male genital tract smooth muscle cells. A “mechanical” mechanism of testosterone action in ejaculation control can also be possible. A hypogonadism-induced reduction in semen volume may perturb the dynamics of the seminal bolus propulsion, possibly explaining ejaculation difficulties in some subjects. In fact, low testosterone directly reduces ejaculate volume, which may result in a lack of stimulation of accessory glands such as the prostate and seminal vesicles, which are well-known androgen targets. Finally, it cannot be excluded that the testosterone differences demonstrated are the consequences of sexual disturbances mirroring differences in sexual behaviour, such as copulation frequency (94).

In conclusion, several possible mechanisms may connect androgen levels with the complex machinery of ejaculation. Clinical studies are currently in progress to further establish the role of testosterone in ejaculatory dysfunction.

The role of prolactin

In a consecutive series of 2,531 patients interviewed using structured interview on erectile dysfunction (SIEDY) (a 13-item tool for the assessment of ED-related morbidities) (95), and Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire (96), for the evaluation of psychological symptoms, low prolactin levels are associated with PE and anxiety symptoms (97). Hypoprolactinaemia may be a consequence rather than a cause of PE. In fact, many psychological disturbances such as stress and frustration for chronic or acquired inability to enjoy sex can provoke a central serotoninergic neuroendocrine imbalance seen in the relative hypoprolactinemia found in patients with PE.

The role of thyroid hormones

The impact of thyroid hyper- and hypofunction in male sexual function has been studied only very recently. This is probably the consequence of: (I) the apparently low clinical significance given to male sexual symptoms in comparison with the systemic effects of thyroid hormone excess and defect; (II) the paucity of clinical studies, as thyroid disease is less common in men; (III) the embarrassment of patients and physicians when discussing sexual dysfunction in the “traditional” setting of the endocrine outpatient clinic (98). However, it has been found a high prevalence of acquired PE in hyperthyroid patients, whereas in hypothyroid subjects the main sexual complaint was delayed ejaculation (43,61). Both ejaculatory dysfunctions reverted on achievement of euthyroidism in the absence of any other treatment for the sexual symptom. Interestingly, suppressed levels of TSH as a marker of hyperthyroidism have been demonstrated in acquired PE (61) but, obviously, not in patients with lifelong PE (99). All these data suggest a direct involvement of thyroid hormones on the physiology of ejaculation.

As the relationship between thyroid hormones and ejaculatory mechanisms is currently unknown, three possible sites of action have been suggested: the sympathetic nervous system, the serotoninergic pathway and the endocrine/paracrine system (100-102). Most manifestations of thyrotoxicosis and sympathetic nervous system activation overlap. This may suggest a similar action on ejaculation, a reflex largely dependent on sympathetic and parasympathetic tone. However, plasma catecholamines and their urinary metabolites are usually normal in hyperthyroidism (100). On the other hand, some studies have found that thyroid hormones augment sensitivity to adrenergic agonists by increasing adrenoceptor density and Gs/Gi protein ratio through an over-activation of adenylate cyclase (101). This leads to increased sympathetic activity with normal circulating catecholamine levels. In hyperthyroid patients, the increased adrenergic tone may trigger both premature and delayed ejaculation, either acting directly on smooth muscle contractility/relaxation or indirectly on anxiety and irritability. The opposite may occur in hypothyroid patients (102). Considering the neuropsychological reactions to thyroid hormone excess (hyperkinesia, nervousness, anxiety, emotional lability), PE may be also a non-specific disease-related complaint, disappearing when a euthyroid state is achieved. However, in light of the widespread distribution of thyroid hormone nuclear receptors within the brain, it can be hypothesized that iodothyronines specifically alter the central serotoninergic pathway (103), leading to diminished ejaculation control. In animals with experimentally-induced hypothyroid states, increased serotonin turnover in the brainstem is consistently reported (104) and thyroid hormone replacement is associated with increased cortical serotonin concentrations and augmentation of serotonergic neurotransmission by desensitization of the serotonin inhibitory 5-HT1A (auto-inhibition) (104). Finally, delayed ejaculation is a common and therapeutically useful side effect of serotoninergic drugs, indicating that this pathway is fundamental for ejaculatory control.

Another way that thyroid hormones may affect the ejaculatory mechanism could be through oestrogen metabolism. Hyperthyroidism increases levels of sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), which binds androgens with higher affinity than oestrogens, leading to a relative hyperoestrogenism (105). It has been demonstrated in hypogonadic rabbits that oestrogens, but not androgens, fully restore oxytocin-induced epididymal contractility, up-regulating oxytocin receptor gene and protein expression, and that deprivation of endogenous oestrogens induces oxytocin hypo-responsiveness (106,107). As oxytocin is closely involved in the ejaculatory mechanism (108) both centrally (109) and peripherally (110), this may account for the close correlation between hyperthyroidism and PE. As an ancillary possibility, thyroid hormone receptors have been described in the animal (111) and human testis (112), and may also be present in other male genital tract structures, triggering ejaculation. Finally, although excluded in the original report (43), some cases of PE in hyperthyroidism are comorbid with ED, which may in turn exacerbate the loss of ejaculatory control (24).

PE and hyperthyroidism

The majority of patients with thyroid hormone disorders experience sexual dysfunction. Studies suggest a significant correlation between PE and suppressed TSH values in a selected population of andrological and sexological patients. The 50% prevalence of PE in men with hyperthyroidism fell to 15% after treatment with thyroid hormone normalization (43). Although occult thyroid disease has been reported in the elderly hospitalized population, it is uncommon in the population who present for treatment of PE and routine TSH screening is not indicated unless clinically indicated (113).

Urologic risk factors

PE and chronic prostatitis

Acute and chronic prostatitis, prostatodynia, or chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) is associated with ED, PE and painful ejaculation (114-118). This syndrome includes urogenital pain, ejaculatory pain, urinary dysfunction, and sexual dysfunction. In the literature, CP has been closely linked with PE (42,117-120). While the co-existence of these conditions is common, a true causal relationship or mechanism has not been established. Prevalence and treatment studies are the cornerstone of this relationship and this data has given researchers insight into potential diagnostic and treatment options for men with PE. The relationship between chronic prostatitis, CPPS and PE is supported by several recently published studies which focus more on epidemiology and largely ignore treatment. Most of these have are limited by poor study design including inconsistent or absent methodologies of microbiological diagnosis of prostatitis and the lack of a validated questionnaire for combined evaluation of chronic prostatitis and sexual dysfunction.

Painful ejaculation is a common symptom of chronic prostatitis or CPPS and is included in all prostatitis symptom scores. In 3,700 men with benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH), painful ejaculation was reported by 18.6% and was associated with more severe lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), and a 72% and 75% incidence of ED and PE respectively (121). Several studies report PE as the main sexual disorder symptom in men with chronic prostatitis or CPPS with a prevalence of 26–77% (119,122-125).

Prostatic inflammation and chronic bacterial prostatitis have been reported as common findings in men with both lifelong and acquired PE (42,120,126). Shamloul and el-Nashaar reported prostatic inflammation and chronic bacterial prostatitis in 64% and 52% of men with PE (120). The 41.4% incidence of prostatic inflammation in men with lifelong PE parallels that reported by Screponi (42), but is inconsistent with the proposed genetic basis of lifelong PE, and assumes the presence of prostatic inflammation from the first sexual experience. Although physical and microbiological examination of the prostate in men with painful ejaculation or LUTS is mandatory, there is insufficient evidence to support routine screening of men with PE for chronic prostatitis. The exact pathophysiology of the link between chronic prostatitis, ED and PE is unknown. It has been hypothesised that prostatic inflammation may result in altered sensation and modulation of the ejaculatory reflex but evidence is lacking (120).

Liang et al. continued to evaluate this association with a study of 1,768 Chinese men with CP and observed that overall sexual dysfunction was present in 49% of this cohort whereas PE, in particular, was present in 26.2% of these patients (119). Duration of CP was shown to be a contributing factor in sexual dysfunctions (PE and ED), where stratification of duration of CP revealed that individuals with ≥19 months of CP-like symptoms have a greater prevalence of PE (44.2%) than those with less than 19 months (24.4%).

In a follow-up study, 7,372 Chinese men were evaluated via cross-sectional survey to determine the correlation between PE and CP and study results demonstrated 15.3% of randomly recruited Chinese men self-reported PE (127). In addition, of those that reported PE, 64.1% reported prostatitis-like symptoms determined by criteria developed by Nickel et al. (128). Men with clinical symptoms of CP suffered from PE at a rate of 36.9%, higher than the general population.

In comparison, a study by Gonen et al. evaluated 66 CP patients and found a PE rate of 77.3%. In comparison, ED was only associated with PE in 15.2% of these patients (123). A similar study evaluated 43 patients with type III prostatitis and found a significant difference between PE prevalence in these patients (67.44%) vs. their control group (40%) (129). An Italian study also evaluated 399 patients with symptoms that were suggestive of CP to determine prevalence of sexual dysfunction within this cohort (125). The authors demonstrated that, 220 (55%) of the patients had ejaculatory dysfunctions, with 110 (28%) of these patients reporting PE. The authors also showed that PE was more frequently associated in patients with high to medium levels of inflammation compared to patients with lower levels of inflammation. This analysis was consistent with Shamloul’s study as noted previously (120). In addition, these researchers stratified prevalence of PE by NIDDK/NIH classification of prostatitis. PE was evenly associated throughout category II (33%), IIIa (29%), and IIIb (21%), respectively (P=0.125).

Several studies have also shown that antibiotic treatment of patients with CP may help to delay ejaculation. Treatment for CP is usually targeted towards gram-negative rods, but other common species may arise, such as Enterococci, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and Pseudomonas species (120,130). The initial account that showed improvement in ejaculatory function through treatment of CP was a study by Boneff (131). Patients were treated with a topical hydrocortisone-antibiotic mixture introduced into the posterior urethra via catheterization after prostate massage. The men who underwent this treatment (n=42) experienced a 52% improvement in ejaculation status, defined by prolongation of copulation for up to 5 minutes. There was a greater benefit from this treatment in patients with co-existing CP (15/22, 68.2%) than just PE alone (7/20, 35%). In a follow-up to their previous prevalence study, El-Nashaar and Shamloul studied a cohort of 145 men who complained of PE for at least 6 months prior to the study (132). Expressed prostate secretion (EPS) positive prostatitis was found in 94 (64.8%) of these men, all of who were asymptomatic antibiotic treatment was given for 1 month and 62 (83.9% of those treated) showed a significant increase in their IELT and no recurrence of PE or CP after 4 months. Zohdy et al. performed a similar study of 210 men with CP symptoms and concomitant PE (133). The goal was to determine clinical parameters that may predict successful outcomes in treatment of CP. They found that 59.0% of the men treated with antimicrobial therapy had a significantly greater increase in IELT, in comparison to an untreated cohort. In addition, there was a difference in outcome between men with acquired PE and lifelong PE, where men with acquired PE responded more effectively to the antibiotic treatment. They also found that men with higher levels of inflammation experienced greater benefits (70.0%) to antibiotic treatment in their IELTs compared to individuals with lower levels (31.4%).

In summary, the urologic literature has shown a higher prevalence of CP or CPPS among PE patients and vice versa. There is also an association between the dimensions of the patient’s CP, i.e., duration of symptoms and levels of inflammation, and the possibility of having PE. Lastly, the beneficial effect of treatment with antibiotics on the improvement of ejaculatory function has been strongly supported.

Together, this evidence strongly supports the idea that CP may be a common cause of both acquired and lifelong PE, thus it should be ruled out, especially in men with associated pelvic pain and/or urinary symptoms. EPS analysis, such as the Meares-Stamey test, is a cheap and easy tool that can delineate such an etiology of the patients with PE (134). Culture of the EPS with speciation of the organism may be beneficial in cases refractory to empiric antibiotic use. Although the connection between prostatic inflammation and pathology of the ejaculatory reflex has been proposed to occur through modulation of the neurophysiologic pathway (135), further studies are required to elucidate the exact mechanism.

Varicocele and PE

Varicocele, the abnormal dilatation of veins in the pampiniform plexus due to retrograde venous flow, has been shown to impact sexual function. Varicoceles are a common urological condition, with the estimated incidence ranging from 15% of the general population to 35% of men with primary fertility issues depending on the screening method (136).

The impact of varicocele on ejaculation has recently been hypothesized as a possible etiology of acquired PE. In an Italian cross-sectional study, Lotti et al. evaluated 2,448 sexual dysfunction patients for the presence of varicocele (137). Their comparison of groups, varicocele vs. no varicocele, showed a significant difference in PE status (29.2% vs. 24.9% in subjects with or without varicocele, respectively), when adjusted for factors such as age, anxiety levels, and prolactin levels. The researchers showed an association between severity of varicocele on Doppler ultrasound analysis and seminal levels of interleukin-8, a surrogate marker for non-bacterial prostatitis. These findings were extrapolated to hypothesize that PE may be a clinical symptom of an underlying inflammatory state caused by varicocele and/or prostatitis. The authors also note that venous congestion through a connection between the testicular and prostatic venous systems may predispose a varicocele patient to prostatitis. Consistent with these findings, there have been preliminary reports from methodologically flawed studies of improvements in men with PE treated with varicoelectomy (138,139).

In conclusion, the presence of varicocele has been shown to be associated with high levels of inflammation in the pelvic area. In the large study conducted by Lotti et al., biological support was given to show the association between the PE and varicocele, yet it is unsure which of these states may predispose a man to the other pathology. More research should be conducted to understand the underlying mechanism that connects these two pathologies.

Circumcision and PE

Circumcision, removal of the penile foreskin, is a routine practice among Islamic and Jewish communities. Considering the loss of high amount of specialized sensory mucosa during this surgery, some authors claimed that circumcision has a negative impact on the overall sensory mechanism of the human penis (140). Some international epidemiologic studies demonstrated lower prevalence for PE in Middle East, confirming this presumption (36). However, clinical studies regarding the penile sensitivity, PE status and sexual satisfaction report conflicting results are not conclusive (11,141-145).

Fink et al. found that adult circumcision was associated with worsened erectile function, decreased penile sensitivity and improved satisfaction without causing any changes in sexual activity (141). Waldinger et al. measured the IELTs of 500 men in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Spain, the United States and Turkey. They observed that Turkish men, who all but two were circumcised (122/124), had significantly lower median IELT (3.7 minutes) compared to the median IELT value of each of other countries (11). Interestingly, the authors also compared circumcised men with not-circumcised men in countries excluding Turkey and observed that IELT values were independent of circumcision status, which has been also confirmed with a latter study (7).

Senkul et al. evaluated the sexual performance of 42 adults before and 12 weeks after circumcision by using Brief Male Sexual Function Inventory (BMSFI) questionnaire and could not demonstrate any difference in sexual function (143). Similarly, recent studies have investigated the role of postcircumcision mucosal cuff length in PE by measuring it in men with and without PE (115,146,147). These authors concluded that neither post-circumcision mucosal cuff length nor circumcision timing is a risk factor for PE. Furthermore, the notion that circumcision might alter penile skin sensitivity and affect sexual function was largely de-bunked by Malkoc et al. who demonstrated that the density of fine nerve endings in the foreskin of circumcised men with PE was not different from that of circumcised non-PE controls (148). Of interest is the report of Alp et al. that not only did circumcision during adulthood not adversely affects ejaculatory function but was associated with significantly longer mean IELTs after circumcision (144). Similarly, Gao et al. reported that adult circumcised men experienced significantly improved IELT, control over ejaculation, and satisfaction with sexual intercourse compared to a control group (P<0.001 for all) (145).

A lack of any relationship between circumcision and risk of PE was confirmed in two extensive systematic analyses of reported data (149,150).

Idiopathic A-PE

The percentage of patients having PE of unknown cause is currently not available. It was frequent in the recent past to consider these patients as psychogenic. However, this is not correct and the term psychogenic should be substituted with that of “idiopathic” PE (151). Future research will provide new pathophysiological elements and the number of subjects with idiopathic PE—probably the majority at the moment—will decrease progressively.

Conclusions

Recent epidemiological and observational research has provided new insights into PE and the associated negative psychosocial effects of this dysfunction. The recently developed multivariate evidence-based ISSM definition of lifelong and acquired PE provides the clinician a more discriminating diagnostic tool and should form the basis of the office diagnosis of lifelong PE.

Although there is insufficient empirical evidence to unequivocally identify the aetiology of PE, there is limited evidence to suggest that acquired PE is most often due to sexual performance anxiety, psychological or relationship problems and/or ED and to a lesser extent, chronic prostatitis, CPPS or hyperthyroidism. Although the absence or deficiency of control in ejaculation is the most common sexual symptom (34), acquired PE remains under-diagnosed and under-treated, despite the fact that it can be successfully treated (152). However, increased medical awareness, careful diagnosis and sub-typing, recognition of the pathogenetic mechanism in individual patients and the forthcoming availability of new drugs specifically designed for PE will give the expert in sexual medicine a new opportunity to treat the severe suffering of many patients.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Mcmahon is a consultant, investigator and speaker for Johnson & Johnson, Janssen Cilag, Menarini, Ixchelsis, Absorption Pharmaceuticals, Neurohealing and Plethora.

References

- Shapiro B. Premature ejaculation: a review of 1130 cases. J Urol 1943;50:6.

- Godpodinoff ML. Premature ejaculation: clinical subgroups and etiology. J Sex Marital Ther 1989;15:130-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD, Hengeveld MW, Zwinderman AH, et al. An empirical operationalization study of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for premature ejaculation. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 1998;2:287-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McMahon CG, Althof S, Waldinger MD, et al. An evidence-based definition of lifelong premature ejaculation: report of the International Society for Sexual Medicine Ad Hoc Committee for the Definition of Premature Ejaculation. BJU Int 2008;102:338-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McMahon CG, Abdo C, Incrocci I, et al. Disorders of orgasm and ejaculation in men. In: Lue LF, Basson R, Rosen R, et al. editors. Sexual Medicine: Sexual Dysfunctions in Men and Women (2nd International Consultation on Sexual Dysfunctions-Paris). Paris, France: Health Publications, 2014:409-68.

- Serefoglu EC, McMahon CG, Waldinger MD, et al. An evidence-based unified definition of lifelong and acquired premature ejaculation: report of the second international society for sexual medicine ad hoc committee for the definition of premature ejaculation. Sex Med 2014;2:41-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD, McIntosh J, Schweitzer DH. A five-nation survey to assess the distribution of the intravaginal ejaculatory latency time among the general male population. J Sex Med 2009;6:2888-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD, Quinn P, Dilleen M, et al. A multinational population survey of intravaginal ejaculation latency time. J Sex Med 2005;2:492-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patrick DL, Althof SE, Pryor JL, et al. Premature ejaculation: an observational study of men and their partners. J Sex Med 2005;2:358-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD, Schweitzer DH. The use of old and recent DSM definitions of premature ejaculation in observational studies: a contribution to the present debate for a new classification of PE in the DSM-V. J Sex Med 2008;5:1079-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD, Schweitzer DH. Changing paradigms from a historical DSM-III and DSM-IV view toward an evidence-based definition of premature ejaculation. Part II--proposals for DSM-V and ICD-11. J Sex Med 2006;3:693-705. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD. History of Premature Ejaculation. In: Jannini EA, McMahon GC, Waldinger MD. editors. Premature Ejaculation. From Etiology to Diagnosis and Treatment. New York: Springer, 2013:5-24.

- Serefoglu EC, Cimen HI, Atmaca AF, et al. The distribution of patients who seek treatment for the complaint of ejaculating prematurely according to the four premature ejaculation syndromes. J Sex Med 2010;7:810-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serefoglu EC, Yaman O, Cayan S, et al. Prevalence of the complaint of ejaculating prematurely and the four premature ejaculation syndromes: results from the Turkish Society of Andrology Sexual Health Survey. J Sex Med 2011;8:540-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Gao J, Liu J, et al. Distribution and factors associated with four premature ejaculation syndromes in outpatients complaining of ejaculating prematurely. J Sex Med 2013;10:1603-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao J, Zhang X, Su P, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with the complaint of premature ejaculation and the four premature ejaculation syndromes: a large observational study in China. J Sex Med 2013;10:1874-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masters WH, Johnson VE. Premature ejaculation. In: Masters WH, Johnson VE, eds. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co., 1970:92-115.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association, 1994:509-11.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization, 1994.

- Metz M, McCarthy B. Coping with premature ejaculation: how to overcome PE, please your partner and have great sex. Oakland (CA): New Harbinber Publications, 2003.

- Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, et al. AUA guideline on the pharmacologic management of premature ejaculation. J Urol 2004;172:290-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colpi G, Weidner W, Jungwirth A, et al. EAU guidelines on ejaculatory dysfunction. Eur Urol 2004;46:555-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD, Zwinderman AH, Olivier B, et al. Proposal for a definition of lifelong premature ejaculation based on epidemiological stopwatch data. J Sex Med 2005;2:498-507. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jannini EA, Lombardo F, Lenzi A. Correlation between ejaculatory and erectile dysfunction. Int J Androl 2005;28 Suppl 2:40-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McMahon CG, Althof SE, Waldinger MD, et al. An evidence-based definition of lifelong premature ejaculation: report of the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) ad hoc committee for the definition of premature ejaculation. J Sex Med 2008;5:1590-606. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc., 2013.

- Reading AE, Wiest WM. An analysis of self-reported sexual behavior in a sample of normal males. Arch Sex Behav 1984;13:69-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nathan SG. The epidemiology of the DSM-III psychosexual dysfunctions. J Sex Marital Ther 1986;12:267-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spector KR, Boyle M. The prevalence and perceived aetiology of male sexual problems in a non-clinical sample. Br J Med Psychol 1986;59:351-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spector IP, Carey MP. Incidence and prevalence of the sexual dysfunctions: a critical review of the empirical literature. Arch Sex Behav 1990;19:389-408. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grenier G, Byers ES. The relationships among ejaculatory control, ejaculatory latency, and attempts to prolong heterosexual intercourse. Arch Sex Behav 1997;26:27-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281:537-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Porst H, Montorsi F, Rosen RC, et al. The Premature Ejaculation Prevalence and Attitudes (PEPA) survey: prevalence, comorbidities, and professional help-seeking. Eur Urol 2007;51:816-23; discussion 824. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jannini EA, Lenzi A. Epidemiology of premature ejaculation. Curr Opin Urol 2005;15:399-403. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giuliano F, Patrick DL, Porst H, et al. Premature ejaculation: results from a five-country European observational study. Eur Urol 2008;53:1048-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, Glasser DB, et al. Sexual problems among women and men aged 40-80 y: prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Int J Impot Res 2005;17:39-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Glasser DB, et al. Sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions after age 40: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Urology 2004;64:991-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montorsi F. Prevalence of premature ejaculation: a global and regional perspective. J Sex Med 2005;2 Suppl 2:96-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Basile Fasolo C, Mirone V, Gentile V, et al. Premature ejaculation: prevalence and associated conditions in a sample of 12,558 men attending the andrology prevention week 2001--a study of the Italian Society of Andrology (SIA). J Sex Med 2005;2:376-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Porst H, McMahon CG, Althof SE, et al. Baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes for men with acquired or lifelong premature ejaculation with mild or no erectile dysfunction: integrated analyses of two phase 3 dapoxetine trials. J Sex Med 2010;7:2231-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hartmann U, Schedlowski M, Krüger TH. Cognitive and partner-related factors in rapid ejaculation: differences between dysfunctional and functional men. World J Urol 2005;23:93-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Screponi E, Carosa E, Di Stasi SM, et al. Prevalence of chronic prostatitis in men with premature ejaculation. Urology 2001;58:198-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carani C, Isidori AM, Granata A, et al. Multicenter study on the prevalence of sexual symptoms in male hypo- and hyperthyroid patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:6472-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adson DE, Kotlyar M. Premature ejaculation associated with citalopram withdrawal. Ann Pharmacother 2003;37:1804-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peugh J, Belenko S. Alcohol, drugs and sexual function: a review. J Psychoactive Drugs 2001;33:223-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McMahon CG, Giuliano F, Dean J, et al. Efficacy and safety of dapoxetine in men with premature ejaculation and concomitant erectile dysfunction treated with a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor: randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III study. J Sex Med 2013;10:2312-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jern P, Santtila P, Witting K, et al. Premature and delayed ejaculation: genetic and environmental effects in a population-based sample of Finnish twins. J Sex Med 2007;4:1739-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Janssen PK, Bakker SC, Réthelyi J, et al. Serotonin transporter promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism is associated with the intravaginal ejaculation latency time in Dutch men with lifelong premature ejaculation. J Sex Med 2009;6:276-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dunn KM, Croft PR, Hackett GI. Association of sexual problems with social, psychological, and physical problems in men and women: a cross sectional population survey. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999;53:144-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mourikis I, Antoniou M, Matsouka E, et al. Anxiety and depression among Greek men with primary erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2015;14:34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar RP, Kumaran AK. Depression and anxiety in men with sexual dysfunction: a retrospective study. Compr Psychiatry 2015;60:114-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar RP, Kumaran AK. The association of anxiety with the subtypes of premature ejaculation: a chart review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2014.16. [PubMed]

- Gao J, Zhang X, Su P, et al. The impact of intravaginal ejaculatory latency time and erectile function on anxiety and depression in the four types of premature ejaculation: a large cross-sectional study in a Chinese population. J Sex Med 2014;11:521-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Son H, Song SH, Lee JY, et al. Relationship between premature ejaculation and depression in Korean males. J Sex Med 2011;8:2062-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaplan HS, Kohl RN, Pomeroy WB, et al. Group treatment of premature ejaculation. Arch Sex Behav 1974;3:443-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaplan HS. PE: How to overcome premature ejaculation. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1989.

- Zilbergeld B. Male Sexuality. Toronto: Bantam, 1978.

- Zilbergeld B. The New Male Sexuality. Toronto: Bantam, 1992.

- Fatt QK, Atiya AS, Heng NC, et al. Validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale and the psychological disorder among premature ejaculation subjects. Int J Impot Res 2007;19:321-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strassberg DS, Mahoney JM, Schaugaard M, et al. The role of anxiety in premature ejaculation: a psychophysiological model. Arch Sex Behav 1990;19:251-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corona G, Petrone L, Mannucci E, et al. Psycho-biological correlates of rapid ejaculation in patients attending an andrologic unit for sexual dysfunctions. Eur Urol 2004;46:615-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little Brown & Co., 1970.

- Figueira I, Possidente E, Marques C, et al. Sexual dysfunction: a neglected complication of panic disorder and social phobia. Arch Sex Behav 2001;30:369-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corretti G, Pierucci S, De Scisciolo M, et al. Comorbidity between social phobia and premature ejaculation: study on 242 males affected by sexual disorders. J Sex Marital Ther 2006;32:183-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bieber I. The psychoanalytic treatment of sexual disorders. J Sex Marital Ther 1974;1:5-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ellis H, Pforzheimer CH. Studies in the psychology of sex. New York: Random House, 1936.

- Finkelstein L. Awe and premature efaculation: a case study. Psychoanal Q 1975;44:232-52. [PubMed]

- Kaplan HS. The New Sex Therapy: Active Treatment of Sexual Dysfunctions. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1974.

- Michetti PM, Rossi R, Bonanno D, et al. Dysregulation of emotions and premature ejaculation (PE): alexithymia in 100 outpatients. J Sex Med 2007;4:1462-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quek KF, Sallam AA, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of sexual problems and its association with social, psychological and physical factors among men in a Malaysian population: a cross-sectional study. J Sex Med 2008;5:70-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahn TY, Park JK, Lee SW, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in Korean men: results of an epidemiological study. J Sex Med 2007;4:1269-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corona G, Mannucci E, Schulman C, et al. Psychobiologic correlates of the metabolic syndrome and associated sexual dysfunction. Eur Urol 2006;50:595-604; discussion 604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Wang X, Gu W, et al. Erectile function of 522 patients with premature ejaculation. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2004;10:15-7. [PubMed]

- Dogan S, Dogan M. The frequency of sexual dysfunctions in male partners of women with vaginismus in a Turkish sample. Int J Impot Res 2008;20:218-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fugl-Meyer K, Fugl-Meyer AR. Sexual disabilities are not singularities. Int J Impot Res 2002;14:487-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- el-Sakka AI. Severity of erectile dysfunction at presentation: effect of premature ejaculation and low desire. Urology 2008;71:94-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corona G, Rastrelli G, Ricca V, et al. Risk factors associated with primary and secondary reduced libido in male patients with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 2013;10:1074-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levine SB. Premature ejaculation: some thoughts about its pathogenesis. J Sex Marital Ther 1975;1:326-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jannini EA, Lenzi A. Introduction to the integrated model: medical, surgical and psychological therapies for the couple. J Endocrinol Invest 2003;26:128-31. [PubMed]

- el-Sakka AI. Efficacy of sildenafil citrate in treatment of erectile dysfunction: impact of associated premature ejaculation and low desire. Urology 2006;68:642-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corona G, Mannucci E, Petrone L, et al. Psycho-biological correlates of free-floating anxiety symptoms in male patients with sexual dysfunctions. J Androl 2006;27:86-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vignozzi L, Filippi S, Morelli A, et al. Regulation of epididymal contractility during semen emission, the first part of the ejaculatory process: a role for estrogen. J Sex Med 2008;5:2010-6; quiz 2017.

- Balercia G, Boscaro M, Lombardo F, et al. Sexual symptoms in endocrine diseases: psychosomatic perspectives. Psychother Psychosom 2007;76:134-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cohen PG. The association of premature ejaculation and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Sex Marital Ther 1997;23:208-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pirke KM, Kockott G, Aldenhoff J, et al. Pituitary gonadal system function in patients with erectile impotence and premature ejaculation. Arch Sex Behav 1979;8:41-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paduch DA, Polzer P, Morgentaler A, et al. Clinical and Demographic Correlates of Ejaculatory Dysfunctions Other Than Premature Ejaculation: A Prospective, Observational Study. J Sex Med 2015;12:2276-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corona G, Jannini EA, Mannucci E, et al. Different testosterone levels are associated with ejaculatory dysfunction. J Sex Med 2008;5:1991-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morelli A, Filippi S, Mancina R, et al. Androgens regulate phosphodiesterase type 5 expression and functional activity in corpora cavernosa. Endocrinology 2004;145:2253-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mancina R, Filippi S, Marini M, et al. Expression and functional activity of phosphodiesterase type 5 in human and rabbit vas deferens. Mol Hum Reprod 2005;11:107-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paduch DA, Polzer PK, Ni X, et al. Testosterone Replacement in Androgen-Deficient Men With Ejaculatory Dysfunction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:2956-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Archer J. Testosterone and human aggression: an evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2006;30:319-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rowland DL. Psychophysiology of ejaculatory function and dysfunction. World J Urol 2005;23:82-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keleta YB, Lumia AR, Anderson GM, et al. Behavioral effects of pubertal anabolic androgenic steroid exposure in male rats with low serotonin. Brain Res 2007;1132:129-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carosa E, Benvenga S, Trimarchi F, et al. Sexual inactivity results in reversible reduction of LH bioavailability. Int J Impot Res 2002;14:93-9; discussion 100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petrone L, Mannucci E, Corona G, et al. Structured interview on erectile dysfunction (SIEDY): a new, multidimensional instrument for quantification of pathogenetic issues on erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 2003;15:210-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crown S, Crisp AH. A short clinical diagnostic self-rating scale for psychoneurotic patients. The Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire (M.H.Q.). Br J Psychiatry 1966;112:917-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corona G, Mannucci E, Jannini EA, et al. Hypoprolactinemia: a new clinical syndrome in patients with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 2009;6:1457-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jannini EA, Ulisse S, D'Armiento M. Thyroid hormone and male gonadal function. Endocr Rev 1995;16:443-59. [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD, Zwinderman AH, Olivier B, et al. Thyroid-stimulating hormone assessments in a Dutch cohort of 620 men with lifelong premature ejaculation without erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med 2005;2:865-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bilezikian JP, Loeb JN. The influence of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism on alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor systems and adrenergic responsiveness. Endocr Rev 1983;4:378-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Williams LT, Lefkowitz RJ, Watanabe AM, et al. Thyroid hormone regulation of beta-adrenergic receptor number. J Biol Chem 1977;252:2787-9. [PubMed]

- Polikar R, Kennedy B, Maisel A, et al. Decreased adrenergic sensitivity in patients with hypothyroidism. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;15:94-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sandrini M, Vitale G, Vergoni AV, et al. Effect of acute and chronic treatment with triiodothyronine on serotonin levels and serotonergic receptor subtypes in the rat brain. Life Sci 1996;58:1551-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bauer M, Heinz A, Whybrow PC. Thyroid hormones, serotonin and mood: of synergy and significance in the adult brain. Mol Psychiatry 2002;7:140-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chopra IJ. Gonadal steroids and gonadotropins in hyperthyroidism. Med Clin North Am 1975;59:1109-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Filippi S, Vannelli GB, Granchi S, et al. Identification, localization and functional activity of oxytocin receptors in epididymis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2002;193:89-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Filippi S, Morelli A, Vignozzi L, et al. Oxytocin mediates the estrogen-dependent contractile activity of endothelin-1 in human and rabbit epididymis. Endocrinology 2005;146:3506-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Filippi S, Vignozzi L, Vannelli GB, et al. Role of oxytocin in the ejaculatory process. J Endocrinol Invest 2003;26:82-6. [PubMed]

- Carmichael MS, Humbert R, Dixen J, et al. Plasma oxytocin increases in the human sexual response. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1987;64:27-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maggi M, Malozowski S, Kassis S, et al. Identification and characterization of two classes of receptors for oxytocin and vasopressin in porcine tunica albuginea, epididymis, and vas deferens. Endocrinology 1987;120:986-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jannini EA, Dolci S, Ulisse S, et al. Developmental regulation of the thyroid hormone receptor alpha 1 mRNA expression in the rat testis. Mol Endocrinol 1994;8:89-96. [PubMed]

- Jannini EA, Crescenzi A, Rucci N, et al. Ontogenetic pattern of thyroid hormone receptor expression in the human testis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:3453-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Atkinson RL, Dahms WT, Fisher DA, et al. Occult thyroid disease in an elderly hospitalized population. J Gerontol 1978;33:372-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bartoletti R, Cai T, Mondaini N, et al. Prevalence, incidence estimation, risk factors and characterization of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in urological hospital outpatients in Italy: results of a multicenter case-control observational study. J Urol 2007;178:2411-5; discussion 2415. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis SN, Binik YM, Carrier S. Sexual dysfunction and pelvic pain in men: a male sexual pain disorder? J Sex Marital Ther 2009;35:182-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JH, Lee SW. Relationship between premature ejaculation and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Sex Med 2015;12:697-704. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao J, Xu C, Liang C, et al. Relationships between intravaginal ejaculatory latency time and national institutes of health-chronic prostatitis symptom index in the four types of premature ejaculation syndromes: a large observational study in China. J Sex Med 2014;11:3093-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang D, Zhang X, Hao Z, et al. Prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in outpatients with four premature ejaculation syndromes: a study in 438 men complaining of ejaculating prematurely. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014;7:1829-36. [PubMed]

- Liang CZ, Zhang XJ, Hao ZY, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in Chinese men with chronic prostatitis. BJU Int 2004;93:568-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shamloul R, el-Nashaar A. Chronic prostatitis in premature ejaculation: a cohort study in 153 men. J Sex Med 2006;3:150-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nickel JC, Elhilali M, Vallancien G, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostatitis: prevalence of painful ejaculation in men with clinical BPH. BJU Int 2005;95:571-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qiu YC, Xie CY, Zeng XD, et al. Investigation of sexual function in 623 patients with chronic prostatitis. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2007;13:524-6. [PubMed]

- Gonen M, Kalkan M, Cenker A, et al. Prevalence of premature ejaculation in Turkish men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Androl 2005;26:601-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beutel ME, Weidner W, Brähler E. Chronic pelvic pain and its comorbidity. Urologe A 2004;43:261-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trinchieri A, Magri V, Cariani L, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Arch Ital Urol Androl 2007;79:67-70. [PubMed]

- Xing JP, Fan JH, Wang MZ, et al. Survey of the prevalence of chronic prostatitis in men with premature ejaculation. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2003;9:451-3. [PubMed]

- Liang CZ, Hao ZY, Li HJ, et al. Prevalence of premature ejaculation and its correlation with chronic prostatitis in Chinese men. Urology 2010;76:962-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nickel JC, Downey J, Hunter D, et al. Prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in a population based study using the National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index. J Urol 2001;165:842-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sönmez NC, Kiremit MC, Güney S, et al. Sexual dysfunction in type III chronic prostatitis (CP) and chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) observed in Turkish patients. Int Urol Nephrol 2011;43:309-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown AJ. Ciprofloxacin as cure of premature ejaculation. J Sex Marital Ther 2000;26:351-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boneff AN. Topical treatment of chronic prostatitis and premature ejaculation. Int Urol Nephrol 1972;4:183-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El-Nashaar A, Shamloul R. Antibiotic treatment can delay ejaculation in patients with premature ejaculation and chronic bacterial prostatitis. J Sex Med 2007;4:491-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zohdy W. Clinical parameters that predict successful outcome in men with premature ejaculation and inflammatory prostatitis. J Sex Med 2009;6:3139-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meares EM, Stamey TA. Bacteriologic localization patterns in bacterial prostatitis and urethritis. Invest Urol 1968;5:492-518. [PubMed]

- Jannini EA, Lenzi A. Ejaculatory disorders: epidemiology and current approaches to definition, classification and subtyping. World J Urol 2005;23:68-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jarow JP. Effects of varicocele on male fertility. Hum Reprod Update 2001;7:59-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lotti F, Corona G, Mancini M, et al. The association between varicocele, premature ejaculation and prostatitis symptoms: possible mechanisms. J Sex Med 2009;6:2878-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed AF, Abdel-Aziz AS, Maarouf AM, et al. Impact of varicocelectomy on premature ejaculation in varicocele patients. Andrologia 2015;47:276-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Asadpour AA, Aslezare M, Nazari Adkani L, et al. The effects of varicocelectomy on the patients with premature ejaculation. Nephrourol Mon 2014;6:e15991. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor JR, Lockwood AP, Taylor AJ. The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision. Br J Urol 1996;77:291-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fink KS, Carson CC, DeVellis RF. Adult circumcision outcomes study: effect on erectile function, penile sensitivity, sexual activity and satisfaction. J Urol 2002;167:2113-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masood S, Patel HR, Himpson RC, et al. Penile sensitivity and sexual satisfaction after circumcision: are we informing men correctly? Urol Int 2005;75:62-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Senkul T, Işer I C. Circumcision in adults: effect on sexual function. Urology 2004;63:155-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alp BF, Uguz S, Malkoc E, et al. Does circumcision have a relationship with ejaculation time? Premature ejaculation evaluated using new diagnostic tools. Int J Impot Res 2014;26:121-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao J, Xu C, Zhang J, et al. Effects of adult male circumcision on premature ejaculation: results from a prospective study in China. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:417846.

- Bodakçi MN, Bozkurt Y, Söylemez H, et al. Relationship between premature ejaculation and postcircumcisional mucosal cuff length. Scand J Urol 2013;47:399-403. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tarhan H, Can E, Akdeniz F, et al. Relationship between circumcision scar thickness, postcircumcision mucosal cuff length measures and premature ejaculation. Scand J Urol 2013;47:328-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malkoc E, Ates F, Tekeli H, et al. Free nerve ending density on skin extracted by circumcision and its relation to premature ejaculation. J Androl 2012;33:1263-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morris BJ, Krieger JN. Does male circumcision affect sexual function, sensitivity, or satisfaction?--a systematic review. J Sex Med 2013;10:2644-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tian Y, Liu W, Wang JZ, et al. Effects of circumcision on male sexual functions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Androl 2013;15:662-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jannini EA, McCabe MP, Salonia A, et al. Organic vs. psychogenic? The Manichean diagnosis in sexual medicine. J Sex Med 2010;7:1726-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McMahon C. Premature ejaculation: past, present, and future perspectives. J Sex Med 2005;2 Suppl 2:94-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]